Wherein I consider Howard French’s opinion piece on the Nail House, entitled “A Couple’s Small Victory a Big Step for China”. This is a follow-up to the previous post on the Nail House case.

I don’t mean to pick on Howard French. OK, maybe I do. But I feel his piece fits many things I wish to discuss about American coverage on China into a neat little package. The nut of his opinion piece, which begins rather breathlessly and then tells us “giddiness should be resisted”, is this:

China is unlikely to be delivered unto a new era by a Gorbachev-like figure. Indeed, since the Soviet meltdown, the leadership has policed itself vigilantly to prevent such a turn and, under President Hu Jintao, has, if anything, grown more conservative.

It seems unlikely to be delivered by China’s intellectuals, either. The country’s scholarly class is for the most part too cowed and too cosseted, too thoroughly co-opted by the system and by the country’s new affluence to make many waves.

Great change won’t come from the country’s peasants, either, even if they have been the locus of mounting effervescence in recent years.

Change, when it comes and whatever form it takes, will be propelled by the fast-rising middle class, by savvy and articulate people who are mindful of their rights, rooted first in property but extending almost seamlessly to questions of speech, of movement and of association.

French believes that Wu Ping and her husband Yang Wu are the harbingers of such change, bold pioneers of a coming new era. I don’t deny that the Nail House tenants were savvy, or that Hu Jintao is not going to be Gorby, or that Chinese scholars nor peasants have not produced some revolutionary movement. There are three assumptions embedded in this article that I’m not so sure about.

- That this was a confrontation between “the people” and “the state”. As French puts it, on the surface this appears to be “two simple citizens against a mighty and murky alliance of an authoritarian state and big development money”. He then says in reality “in a society where people have been effectively atomized … they also figured out how to glue millions of discrete individuals together in sympathy for a cause not directed from above.” So then we are to understand this was a popular movement against the state, not two lone individuals. But was it really against the state? Certainly the Chongqing officials/developers were cast as the opposition here, but Wu Ping and Yang Wu invoked the nation and the law as their protection. The national government was not the target here, but the local. And the national government is not, as many Americans believe, monolithic. CCTV interviewed Wu Ping just before the March 22nd deadline. Even the local government was not simply set against the tenants – after all, negotiations dragged out for three years before the story exploded in the media. While the developer no doubt played dirty tricks, some elements of the Chongqing government must have functioned to some degree in protecting the tenants, otherwise the house would have been long since demolished. But instead of portraying this as a tangled web of interests both within and without the local community, government, media and national goverment, French tells us a simplified David and Goliath tale, to the readers loss.

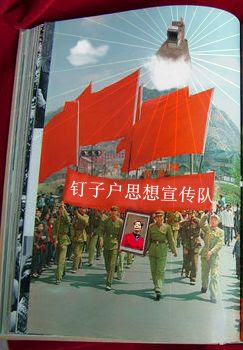

- That there is a new era on the horizon. James Mann, in his book The China Fantasy, suggests that American perspectives on China have long been dominated by two competing visions of the future: The Soothing Scenario, a democratized China brought about by trade and globalization, and The Upheaval Scenario, in which China collapses due to any number of internal problems. Mann then posits a third scenario, in which China does neither, and more or less continues doing what it already does, namely be authoritarian, only richer. Mann is not the first to suggest this. French’s article seems to imply a bit of both of the first two scenarios, suggesting that trade and economic reform has created a middle class that will generate upheaval, forcing the government to adapt and perhaps even democratize or face a collapse. He ends his piece quoting Zhao Ziyang, who vanished from the leadership after supporting the students at Tiananmen, saying that the works of Mao would have to be relegated to a museum. But the underlying assumption is that there will be a “new era” at all.

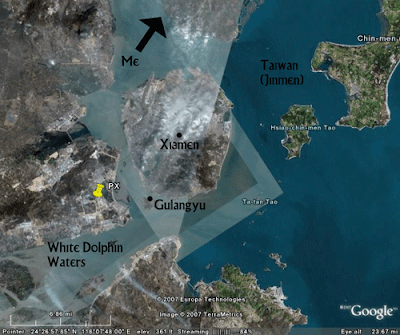

- That the new era, or two or three, didn’t already arrive long ago. The middle class in China, for several years now, have been “mindful of their rights” as French puts it. Freedom of speech, movement and association has grown tremendously particularly for those with money. Rather than perceiving this as a trend that started long ago, and with at least some awareness by the government of what they were inviting, if they are at all as smart as French says they are, French sees it as being on the horizon. There’s no consideration that these events actually exist along a continuum of gradual changes ever since Deng Xiaoping’s southern tour. Or that there are more recent antecedents to the Nail House story: The Huananxincheng Story a year earlier had much of the same criteria: local middle class man seeks to defend his rights, is beaten by local provincial authorities, and then CCTV makes it national, forcing the provincial authorities to address it. But sometimes I feel like many in America have “Tiananmen Fever” – as if the democratic revolution they saw on TV was put on pause, and they are waiting for someone to pick up the remote and press play again.

I wonder at the fact that I find points to agree with Lu Gaofeng’s China Youth Daily editorial, Media Overexcited in Nail House Coverage – I haven’t decided if Sina.com’s cash prizes for photos was a good idea or not – and Chinese blogger Xiaowu’s commentary, in which he says:

So I have argued that what really happened is not the same as the audience watched or read from the media. It is not about a tough resident fighting against government’s violence and power. It is not an incident of human rights or protecting civil rights. It is definitely not an evidence to show that “wind may come in, rain may come in, but the king may not… …” is true in China. There is a logic widely known operating. The local government did not take away this house immediately because some stronger forces working behind. From the TV news report, the woman of the office of demolition was not as arrogant and aggressive as the victim. There are some reasons for it. Imagining the victim as a heroine of human rights is only a wishful thinking of ordinary people. … …

UPDATE: Philip Bowring in the Asia Sentinel has a relevant article entitled “China’s Middle Class: Not What You Think It Is”, in which he points to the work of UBS economist Jonathan Anderson who crunches the number and believes that the number of Chinese citizens that could arguably be urban middle class, that is those who can afford “a mortgaged apartment, a car, a computer, the occasional karaoke visit”, comes out to 70 million. If that’s the case, it seems difficult to believe they will be at the forefront of radical change, and as James Mann suggests, they may actually be the most likely to be for the status quo.