Radovan Karadžić has been arrested in Belgrade, where he has been hiding right under everyones noses under an assumed identity of a mystic healer. On the official Serbian/English website of his alter ego, Dr. Dragan Dabic, he claims he once “settled in China where he specialized in alternative medicine, with a special emphasis on the mind-body control, meditation, Yoga, spiritual cleansing, as well as Chinese herbs.” He also lists his favorite ten Chinese proverbs. Fittingly, the last one is “the one who gives up his own should dig two graves”, considering his crimes and motives.

Karadžić was Supreme Commander of Bosnian Serb forces during the war in the Balkans, and is accused of war crimes, including the siege of Sarajevo and the Srebrenica massacre. I actually followed the Balkans long before I was interested in China. In 1993, I learned the dying art of microfiche putting together a paper on the war, and came to pretty depressing conclusions about attitudes on all sides. The same year I attended the World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna, where former Yugoslavian activists were handing out wanted posters for Karadžić long before the real wanted posters started appearing across Serbia. In 2005, I finally got to visit Croatia, Bosnia and Serbia.

In Croatia I island hopped on the Adriatic coast. Lonely Planet had just ranked Croatia its number one destination, and the New York Times had a piece on the nightlife on the island of Hvar while I was staying there. I had no idea I was stumbling into this. I had been in Budapest and wanted desperately to hit the nearest beach after 3 years of being landlocked in Xinjiang. A Russian acquaintance pointed me towards Split, and I went. I found bits of connections to China all along the way from Split to Belgrade, from little “Chinese Shops”, to the alleged birth place of Marco Polo on the island of Korcula.

Arriving in Hvar, I found the front page headline was about Paris Hilton being spotted on the beaches of Dubrovnik. A pair of older doctors I met in a water taxi, Vesna and Zoran, informed me which boat anchored off the harbor contained the King of Jordan. The docks were lined with million dollar yachts. The Croatian coast seemed more Italian than anything else to me, and not at all a country recovering from civil war. Vesna and Zoran, however, told me otherwise, after coffee after they were kind enough to help me treat a sea urchin sting. They were from Zagreb, the capital, which they told me was far more industrial and Soviet-esque. Zoran had been a medical officer during the war, and began to tell me several things I would hear across all three nations: Slobodan Milosevic, or Slobo, had realized the power of nationalism and television when he, a relatively minor official, was sent to Kosovo in 1987 because no one else wanted to go. “You saw he was frightened”, Zoran told me, but when Slobo blurted out that “no one will humiliate the Serbs” and the crowd cheered, “you saw his face change. He discovered his wings.” The Serbians, I heard in Croatia, Sarajevo and Belgrade, had been fooled by television. He also told me something else that would be echoed later: things were better under Tito. “For many years as an intellectual, I opposed Tito and the Communists. But we built submarines, jets – not as good as F-16s, but good. We had a market larger than Australia. We had an industrial base.” “Under Tito, we were happy. He lived a poor man. When he died, all he left to his son – his son with one arm, having lost the right one fighting Germany alongside the Red Army, was a small vineyard… When Tito died, a blue train carried him back to Belgrade”. At this point, Zoran was holding back tears. “Half a million people stood for him in Zagreb. They stood along the whole train, Croatian, Serbian, Bosnian.” Before we parted, he said I should go to Belgrade. “You’ve heard my story, you should hear theirs.” He had also just told me people died falling through rusted holes in the trolleys, crushed between wheel and track.

My first stop in Bosnia was Mostar, home of the bridge by the same name. Mostar seemed better off than alot of Bosnia, because of its proximity to Dubrovnik, the tourist cache of its bridge, and what appeared to be a fairly large university student population. Most of the places I went in the former Yugoslavia, it seemed like the population was predominantly under 35. The town still had a sort of Muslim/Christian divide on either side of the river, but everyone I spoke to seemed to get along fine, now that the “madness” had passed.

Inside the mosque in Mostar

From Mostar I traveled to Medjugorje, a small village that has become famous because of six Catholic teenagers who claimed to have seen the Virgin Mary on a hilltop. In a sort of Vatican version of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell”, the Pope has neither recognized it nor condemned it. When we told our Mostar sobe (homestay) landlady, she said in the bit of German she knew “Ah. Kleine California.” Irish, German, American and others flock her on on pilgrimmage to walk to the top of the mountain, then come down to gift shops with endless rows of Virgin Mary statues and bric-a-brac, like plaques in English with “Top Ten Reasons to Stay Roman Catholic”, and holographic cards that alternate between Jesus’ face and the Shroud of Turin (a friend who bought one in Turin said the shopkeepers pitch was to flip it back and forth saying “Jesus alive, Jesus dead! Jesus alive, Jesus dead!”)

There are little “Chinese Shops” like this dotted from Sarajevo to Belgrade.

No, that’s not me.

In Sarajevo, I visited the Tunnel Museum. The tunnel was constructed underneath the airport runway, which was under the control of UN forces during the siege. It allowed the transfer of arms, people and supplies despite both the Serbian blockade and the international arms embargo. Sarajevo seemed a fairly sedate place, except for the cafes, which were packed every afternoon with hip young people and televised football.

After Sarajevo, I visited Srebrenica, almost precisely 10 years after the massacre.

Many were executed in the warehouses across from the cemetary and memorial.

Karadžić had alot to do with this.

The haunting and elegant outdoor mosque at the cemetary.

The town of Srebrenica was still mostly in ruins. The only recent additions seemed to be NGOs…

In war-scarred buildings.

In Belgrade, I was determined to visit the Chinese embassy that was bombed in 1999. It still stands, and there were still memorial services apparently. The embassy building is in Novi Beograd, where the streets are massively wide. Across the street are enormous apartment blocks and behind the embassy lies a sprawling low level government building, which I think (but am not certain) is/was the building the US government claimed it wanted to target. Saying its 300 meters away (the Wikipedia article also says the FDSP building was a block away, which would be really far, these are big blocks) seems a stretch, as it has alot of grass around it. Nothing stood to the left or right of the embassy in 2005, and I wonder what was there in 1999. I had always imagined the embassy stood in a denser, older neighborhood, some early twentieth century building on a busy pedestrian street. The bomb hit to the southwest of the building (the southern side has the huge crack in it). I don’t buy the argument that the U.S. hit the embassy deliberately to intimidate China, but I’m more then willing to consider that it may have been deliberate for other reasons, such as the claim the U.S. believed the embassy was relaying Serbian radio traffic. My first instinct, though, is that it was a matter of carelessness or error.

I’m not going to try to translate these. Anyone interested?

A small side road in front of the embassy is now used for driving lessons.

The new Chinese embassy is not far from Tito’s Mausoleum, in a park, surrounded by the mansions of wealthy elites.

Novi Beograd is full of huge apartment blocks like this one. Something similar lies across from the embassy.

I also visited the Chinese Market in New Belgrade, but unfortunately have no photos. Its a small shopping mall full of Chinese immigrants, mostly from Fujian I believe, who sell 99 cent batteries, cheap clothes, towels, salt and pepper shakers, radios, clothes hangers, etc. Apparently alot of Belgrade goes there for cheap items, and it has a Chinese restaurant with the most awful, oily Sichuan food I’ve ever had in my life. One interesting thing I noted (and a local friend confirmed) was that some of the Chinese shops appeared to employ Roma. The Roma in Belgrade, like alot of Europe, are not considered trustworthy or hard-working, so this kind of stuck out a bit. I found China in another place: the Mausoleum of Tito. To the right of his tomb is a room of Chinese furniture given to him by the Chinese government. I don’t know in particular whether it was Mao, Zhu, Deng or someone else.

From a student art exhibit in a museum once dedicated to Tito’s cars and a large map of world Communist revolutions.

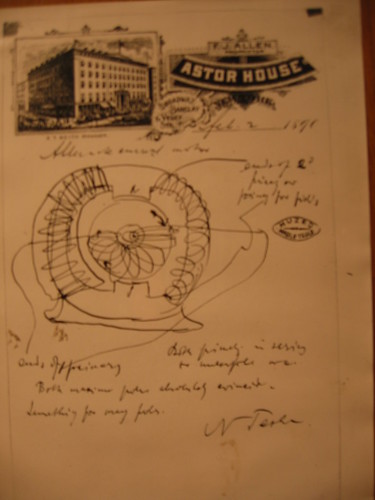

The tools and sketches of Nikolai Tesla from the Tesla Museum

Two weeks before the bombing of the embassy, the Radio and Television building was bombed. A memorial nearby for the 16 technicians killed in the attack asks “Why?”, and a local friend told me that the question is not “Why did the Americans bomb it?”, but “Why did the Serbian government say it was not a target when they knew it was?” My friends, at least, believed that the Serbian government allowed it to happen to drum up support. They were at the neighboring theatre, where every Friday night there was a wicked salsa dance party in the shadow of the wreckage.

You cannot know what took place in Bosnia even if you visit the place yearly. It’s all for nothing and the information you have provided about Srebrenica is shallow, a one big platitude, mainstream coverage. “Karadzic had a lot to do with this,” good enough for a soccer mom, but that is as far is it goes.