Back in 2004, a news surfaced about CCTV producing it’s first ever science fiction TV show, Angel Online (天使在线). Sina.com.cn had a whole page devoted to it, complete with quote from the director and Chinese scifi writers talking about the need for science fiction in encouraging creativity, and how this would be China’s Star Wars, Matrix and Heat Vision and Jack rolled into one. (You can read a synopsis here, in which artificial intelligence “Net Babies” (网婴) become all the rage, only for one becomes all-powerful on the Internet). And then it became impossible to find anymore news about it – and not only because 天使在线 is the name of a popular MMO gaming webpage. Then I noticed that Seed Magazine’s China Science section mentioned it last September, and I figured I’d check Baidu again. Turns out in January Sina reported that Jackie Chan might join the show?!?? I’ll believe it when I see it, since in 2004 principal photography was suppose to start in 2005 and now Sina says it’ll be out in 2008. But in the mean time, it turns out a major fan has been working on a Chinese machinima movie: 原始地带 ZONE OF BARBARISM! You can watch a short confusing clip here, which consists of helicopter animations, the back of a head that could be Chuck Norris, and a gorilla. Perhaps it involves a search for the mysterious 野人 of 神农架? Personally, I love the description:

Author: davesgonechina

Filmmaker Jia Zhangke Arrested! Plus: Life Imitating Art

In the movie Karmic Mahjong, or 血战到底, that is. Jia Zhangke (贾樟柯), film festival darling and director of the recent Still Life (三峡好人) is pictured here being arrested by none other than Wang Xiaoshuai (王小帅), director of Beijing Bicycle (十七岁的单车). You can see the brief cameo scene, with JZK as a hostage-taking mugger and WXS as negotiator at tudou.com about 3 minutes in.

Captions, anyone?

UPDATE: Also of interest, Little Bridge has a post about a Chinese woman who has advertised online that she will carry someone’s baby to term for 500,000 yuan. Curiously enough, there is a character in 血战到底 who regrets carrying and then giving up her son to a mobster… for 500,000 yuan. Life imitates art? Has this girl seen 血战到底?

Why Xinjiang is not like Iraq, or a Major Al Qaeda Front

We interrupt our regular discussion of more fun things to discuss reports about terrorism in Xinjiang. This time, there’s an essay in the PacNet newsletter, available at the Time Magazine China Blog, by one Martin I. Wayne, a China Security Fellow at the National Defense University’s Institute for National Strategic Studies. Dr. Wayne, however, is a hard man to find. Not only is he not listed on the INSS staff directory, he doesn’t show up anywhere on Google. Not an easy feat these days. His book, “Understanding China’s War on Terrorism”, brings up nothing as well. It’s a shame, because I’d like to know more of his findings. On with the fisking (I’ve changed it so Wayne is in italics, I am not):

Al Qaeda’s China Problem by Dr. Martin I. Wayne

Al Qaeda has a China problem, and no one is watching. Despite al Qaeda’s significant efforts to support Muslim insurgents in China, the Chinese government has succeeded in limiting popular support for anti-government violence.

I have yet to see, beyond the occasional lip service provided in roughly two video statements (one here, transcrit of Zawahiri’s 2006 statement at Laura Mansfield’s site), “significant support” by Al Qaeda documented publicly by anyone.

The latest evidence came on Jan. 5, when China raided an alleged terrorist facility in the country’s Xinjiang region, near borders with Pakistan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan. According to reports, 18 terrorists were killed and 17 were captured, along with 22 improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and material for thousands more.

IEDs is a misleading term. First because IED has now become the common term for roadside bombs. Second because the term used by Xinjiang officials has been 手雷, which literally refers to “hand thunder”, or a grenade. IED in Chinese, according to press reports, is 路边炸弹, or literally “roadside bomb”. Chinese reports about the seizure of 手雷 in Xinjiang have been curious, as statistics appear contradictory. A brief review:

- CCP-backed Hong Kong newspaper Takungpao reported August 30, 2006, that according to incomplete statistics, 6,540 grenades had been seized by authorities between 1990 and 2006. (English version ).

- However in 2004, Xinjiang Party Chairman Wang Lequan claimed in one raid in 1999 that over 6,000 hand grenades had been found. (article at news.gzwindow.com now unavailable except through Google Cache; article also captured by chinesenewsnet (blocked in China), and later reposted on the Tiexue BBS.)

- Then, in January 2002 and December 2003, two reports, one which was an eight thousand character essay, both refer to a raid uncovering over 4,500 grenades. The first essay claims it was in Hotan, in 1999, while the second essay implies it occurred after 9-11.

Chinese reportage on terrorism is notoriously problematic, at times imprecise, or simply fabricated.

… now why on Earth might one think that?

For the skeptics, photos of the policeman killed in the raid were also released, showing emotional relatives amid a sea of People’s Armed Police paying their final respects. Ironically, China’s ability to successfully kill or capture militants without social blowback demonstrates the significant degree to which China has won the population’s “hearts and minds,” however begrudgingly.

And here the author chooses a terrible phrase to use. While one could argue that the PRC has successfully prevented widespread insurgency or unrest since 1997, winning “hearts and minds” is not what most visitors to Xinjiang will mark. The hearts and minds are quite against the Chinese, as a government and as a people. It is not a zero-sum game between a) the Party and b) violent ideologues. Most Uyghurs are neither, but Dr. Wayne has chosen to omit this.

China’s successful efforts to keep the global jihad from spreading into its territory present a real challenge for al Qaeda. The organization reportedly trained more than 1,000 Uyghurs, a Turkic ethnic group that is predominantly Muslim, in camps in Afghanistan prior to 9/11. In late December, al Qaeda’s number two, Dr. Ayman al-Zawahiri, called for action against “occupation” governments ruling over Muslims, including reference to the plight of Uyghurs in western China.

The number of Uyghurs trained in Afghanistan is not easily obtainable, for obvious reasons. According to Strategic Insights, a monthly electronic journal produced by the Center for Contemporary Conflict at the Naval Postgraduate School, Gaye Christoffersen wrote:

“Beijing’s estimates of the extent of al Qaeda influence were overstated, with claims that there were 300 Uyghurs in Afghanistan in late 2001 and that all Uyghur separatists in Xinjiang were linked to al Qaeda. Later this was reduced to claims of 100 Uyghurs in Afghanistan, and altogether 1000 Uyghurs in Xinjiang trained by al Qaeda and the Taliban. That claim is supported by the United National Revolutionary Front of East Turkestan (UNRF), which also claimed that there were more than 100 Uyghurs in Afghanistan at that time helping the Taliban.”

This would be a good time to mention that the Chinese government has, as Dr. Wayne may be doing here, conflated different Uyghur terrorist organizations. The PRC has primarily referred to the East Turkestan Independence Movement, or ETIM – the only group linked to Al Qaeda through its now deceased leader Hasan Mahsum, who was killed by Pakistani forces in 2003 during a raid on an Al Qaeda hideout. Here I refer to probably the most authoritative document existing about evidence of Uyghur terrorism, Violent Separatism in Xinjiang: A Critical Assessment(PDF) by James Millward. In analyzing the 2002 8,000 Character Essay conservatively titled “East Turkistan Terrorist Forces Cannot Get Away with Impunity”, Dr. Millward points out:

“Because in Chinese the compound “Dongtu” (East Turkistan) is used both in a generic sense, for all “East Turkistan” groups, and as a specific abbreviation for any name beginning with “East Turkistan,” the result is ambiguity over whether a given act was committed by a specific group known to espouse a separatist line (such as the East Turkistan Liberation Organization, or ETLO) or by unknown perpetrators whom the authors of the document claim, without providing evidence, to be East Turkistan separatists. Moreover, the English version of the document uses the singular form (“the ‘East Turkistan’ terrorist organization”) for terms that in Chinese (which lacks a definite article) are generic and possibly either singular or plural. The document thus implies that there is a unified East Turkistan terrorist organization of considerable strength. From all other indications, however, this is not the case.”

Millward goes on to point out that US government endorsed this sloppiness when it placed the ETIM on the terrorist watch list “thus attributed to ETIM specifically all the violent incidents of the past decade in Xinjiang that the PRC document itself blames only on unnamed groups or on ETLO.” As for the UNRF, the only other source to support the 1,000 trainee claim besides the PRC, Millward notes: “the 80-year-old leader Mukhlisi is now largely discredited and resented by other exile Uyghur groups in Central Asia for exaggerating Uyghur involvement in militant activities—as he did, for example, in March 1997 by announcing that the Urumqi bombings (on the day of Deng Xiaoping’s memorial) were the work of his own and two allied Uyghur groups in Kazakhstan, by all accounts a false claim not even credited by the PRC.”

There is also a question about to what extent the Chinese government attributes what might be criminal acts for financial or other motives. The Yining Riot, also discussed in Millward’s essay, is a clear example. There has never been any evidence submitted that suggests that any sort of terrorist group was involved except PRC allegations that the East Turkestan Islamic Party of Allah provoked it (the ETIPA does not seem to exist beyond this one-off). Dr. Wayne would seem to have failed to differentiate between the claims of the PRC, the UNRF and others, and perpetuated a dangerously oversimplified picture.

Yet despite this commitment of resources and rhetorical energy, Uyghurs across Xinjiang’s social spectrum explain that violent resistance is no longer a viable path. Many Uyghurs in Xinjiang believe that insurgents worsen Uyghurs’ plight by making the Chinese more fearful, thereby more repressive.

This is, in my opinion, a fair and accurate statement. I would certainly not, however, characterize it as winning “hearts and minds”. This is what people crushed by authoritarian repression and fear say. They respond out of fear of what the PRC would do to them, not out of respect (unless you are someone who believes fear is the only form of respect, as regrettably some American conservatives apparently do). Most importantly, Wayne makes a very large mistake: he conflates the Uyghurs with both Al Qaeda and Iraq. Al Qaeda and Iraqi insurgents are not the same to begin with, and comparing it to the Uyghurs is even worse. The Uyghurs, as Millward points out, have long had ethnic nationalist aspirations, as opposed to religious ideological ones. He states:

“The participants in acts of anti-Chinese resistance and their motivations have been varied. Insofar as there is a common denominator, for the twentieth century this has been Uyghur nationalism—sometimes colored by Islam as a basic part of Uyghur culture but not arising from a desire to create an Islamic state per se.”

And this is precisely why Al Qaeda is not a good model for considering Uyghur terrorism, such as it is, and especially inappropriate for judging the views of Uyghurs who do not support violent or ideological means. Uyghurs overwhelmingly harbor nationalist dreams connected most intimately to Turkey, not the Arab states. Pan-Turkicism is an ethnic phenomenon that goes against Al Qaeda’s most basic beliefs. Islam has usually taken the role of garnish, not main dish. Millward then goes on to explain why it’s so tempting to look at Xinjiang through an Islam-centric lens:

“Despite this ethnonationalist, as opposed to religious, basis to Uyghur separatism in Xinjiang, journalists seem to take interest in Xinjiang primarily because it is a majority Muslim area. The reasons for this are clear. I myself once cowrote a magazine article titled “Why Islam Troubles China Too,” capitalizing on the fact, startling and intriguing to a general readership, that China has a large Muslim population in Xinjiang. This fact serves as a perennial hook for pieces about Xinjiang and the Uyghurs, one that seems even more compelling in the aftermat of the 2001 terrorist attacks in the United States, because it fits Xinjiang into the ongoing global narrative of “Islamic terror.” Since stories about Xinjiang usually appear as sporadic features, rather than part of continuing coverage, journalists return to this hook repeatedly with each piece about the region.”

This is part of what I consider the Xinjiang strain of “I Can’t Believe It’s Not China!” journalism.

Why Uyghurs have not radicalized in large numbers is a matter of debate, but certainly one reason is they have not been given the chance – and this is because of China’s strict control that Dr. Wayne claims has been relaxed in exchange for “soft power”. While the PRC may have eased on mass arrests or excessive force, they have not relaxed when it comes to strictly policing religion and free speech. When imams are trained by the state and surveilled, it makes it quite difficult for one of them to preach an extremist message. On the other hand, it makes it impossible for anyone to engage in civil society building or public debate. Dr. Wayne clearly understands this: “The Chinese government purged separatist sympathizers from local governments and attempted to remove political dissent from religious worship“, yet seems to believe that this control has somehow slackened. It has not, just has similar control has not slackened for any other part of the PRC (though it may be more rigid in Xinjiang).

At the same time, availability of Uyghur language education was broadened and Beijing sought to expand economic development in Xinjiang, which was viewed as the key to success.

Dr. Wayne seems unaware of the growing pressure for Uyghurs to study in Chinese language schools. He also continues on about Zawahiri’s message, which mentioned Xinjiang briefly in a list including Chechnya and Spain. He also spent several paragraphs talking about Palestine, but Al Qaeda has yet to show a very strong presence in the Territories. In fact, Hamas has told him to please go away. Another melodramatic bit of flair Wayne uses is to claim “Local men who traveled to Afghanistan to fight the Soviets returned home with new skills and attempted to ply their trade. Young Uyghurs were inspired by the power of men, armed with Allah and AK-47s, to defeat a superpower.” A number of Uyghurs, however, fought on the Soviet side. I met one in Urumqi who had a Russian tank tattooed on his chest – because he was in one. He was part of the large exodus of Uyghurs to Soviet Central Asia who eventually returned after the 80s.

The raid in Xinjiang upon a group taking mining explosives and building IEDs represents a threat similar to the attacks of Madrid and London: home-grown individuals, radicalizing, building weapons with supplies at-hand.

This sort of blurring of distinctions is precisely one of the biggest problems with the “War on Terror”. To compare angry young immigrant populations inspired by extremists zealots to an angry indigeneous population demanding political freedom is to miss the very key elements necessary to understanding what is going on.

The contrast between China’s project in Xinjiang and U.S.’s actions in Iraq is stark: where China realized that local politics was a key factor for strategic effectiveness, the U.S. has focused on targeting an ever-growing pool of insurgents and terrorists. China’s ultimate success in frustrating al Qaeda’s designs on Xinjiang rests upon its recognizing and responding to the political nature of the threat.

And so we come to Iraq, and here is the biggest failure to make a distinction I could possibly imagine. On the one hand we have China’s “project in Xinjiang”, which is to maintain control over an internal province so as to permanently keep it within their borders under an authoritarian government. On the other hand we have America’s “actions in Iraq”, where the goal, ostensibly, is to leave after establishing a democratic, self-governed nation. China’s efforts in Xinjiang have to been to prevent any kind of unified social movement, whether it be Rebiya Kadeer’s peaceful one or Hasan Mahsum violent one, so that society is organized by Beijing, not the public. If the U.S. wants to make Iraq into a repressive version of Puerto Rico, then Dr. Wayne is right – there are lessons to learn from the PRC.

OK, OK, back to more fun stuff.

Why Xinjiang is not like Iraq, or a Major Al Qaeda Front

We interrupt our regular discussion of more fun things to discuss reports about terrorism in Xinjiang. This time, there’s an essay in the PacNet newsletter, available at the Time Magazine China Blog, by one Martin I. Wayne, a China Security Fellow at the National Defense University’s Institute for National Strategic Studies. Dr. Wayne, however, is a hard man to find. Not only is he not listed on the INSS staff directory, he doesn’t show up anywhere on Google. Not an easy feat these days. His book, “Understanding China’s War on Terrorism”, brings up nothing as well. It’s a shame, because I’d like to know more of his findings. On with the fisking (I’ve changed it so Wayne is in italics, I am not):

Al Qaeda’s China Problem by Dr. Martin I. Wayne

Al Qaeda has a China problem, and no one is watching. Despite al Qaeda’s significant efforts to support Muslim insurgents in China, the Chinese government has succeeded in limiting popular support for anti-government violence.

I have yet to see, beyond the occasional lip service provided in roughly two video statements (one here, transcrit of Zawahiri’s 2006 statement at Laura Mansfield’s site), “significant support” by Al Qaeda documented publicly by anyone.

The latest evidence came on Jan. 5, when China raided an alleged terrorist facility in the country’s Xinjiang region, near borders with Pakistan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan. According to reports, 18 terrorists were killed and 17 were captured, along with 22 improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and material for thousands more.

IEDs is a misleading term. First because IED has now become the common term for roadside bombs. Second because the term used by Xinjiang officials has been 手雷, which literally refers to “hand thunder”, or a grenade. IED in Chinese, according to press reports, is 路边炸弹, or literally “roadside bomb”. Chinese reports about the seizure of 手雷 in Xinjiang have been curious, as statistics appear contradictory. A brief review:

- CCP-backed Hong Kong newspaper Takungpao reported August 30, 2006, that according to incomplete statistics, 6,540 grenades had been seized by authorities between 1990 and 2006. (English version ).

- However in 2004, Xinjiang Party Chairman Wang Lequan claimed in one raid in 1999 that over 6,000 hand grenades had been found. (article at news.gzwindow.com now unavailable except through Google Cache; article also captured by chinesenewsnet (blocked in China), and later reposted on the Tiexue BBS.)

- Then, in January 2002 and December 2003, two reports, one which was an eight thousand character essay, both refer to a raid uncovering over 4,500 grenades. The first essay claims it was in Hotan, in 1999, while the second essay implies it occurred after 9-11.

Chinese reportage on terrorism is notoriously problematic, at times imprecise, or simply fabricated.

… now why on Earth might one think that?

For the skeptics, photos of the policeman killed in the raid were also released, showing emotional relatives amid a sea of People’s Armed Police paying their final respects. Ironically, China’s ability to successfully kill or capture militants without social blowback demonstrates the significant degree to which China has won the population’s “hearts and minds,” however begrudgingly.

And here the author chooses a terrible phrase to use. While one could argue that the PRC has successfully prevented widespread insurgency or unrest since 1997, winning “hearts and minds” is not what most visitors to Xinjiang will mark. The hearts and minds are quite against the Chinese, as a government and as a people. It is not a zero-sum game between a) the Party and b) violent ideologues. Most Uyghurs are neither, but Dr. Wayne has chosen to omit this.

China’s successful efforts to keep the global jihad from spreading into its territory present a real challenge for al Qaeda. The organization reportedly trained more than 1,000 Uyghurs, a Turkic ethnic group that is predominantly Muslim, in camps in Afghanistan prior to 9/11. In late December, al Qaeda’s number two, Dr. Ayman al-Zawahiri, called for action against “occupation” governments ruling over Muslims, including reference to the plight of Uyghurs in western China.

The number of Uyghurs trained in Afghanistan is not easily obtainable, for obvious reasons. According to Strategic Insights, a monthly electronic journal produced by the Center for Contemporary Conflict at the Naval Postgraduate School, Gaye Christoffersen wrote:

“Beijing’s estimates of the extent of al Qaeda influence were overstated, with claims that there were 300 Uyghurs in Afghanistan in late 2001 and that all Uyghur separatists in Xinjiang were linked to al Qaeda. Later this was reduced to claims of 100 Uyghurs in Afghanistan, and altogether 1000 Uyghurs in Xinjiang trained by al Qaeda and the Taliban. That claim is supported by the United National Revolutionary Front of East Turkestan (UNRF), which also claimed that there were more than 100 Uyghurs in Afghanistan at that time helping the Taliban.”

This would be a good time to mention that the Chinese government has, as Dr. Wayne may be doing here, conflated different Uyghur terrorist organizations. The PRC has primarily referred to the East Turkestan Independence Movement, or ETIM – the only group linked to Al Qaeda through its now dec

eased leader Hasan Mahsum, who was killed by Pakistani forces in 2003 during a raid on an Al Qaeda hideout. Here I refer to probably the most authoritative document existing about evidence of Uyghur terrorism, Violent Separatism in Xinjiang: A Critical Assessment(PDF) by James Millward. In analyzing the 2002 8,000 Character Essay conservatively titled “East Turkistan Terrorist Forces Cannot Get Away with Impunity”, Dr. Millward points out:

“Because in Chinese the compound “Dongtu” (East Turkistan) is used both in a generic sense, for all “East Turkistan” groups, and as a specific abbreviation for any name beginning with “East Turkistan,” the result is ambiguity over whether a given act was committed by a specific group known to espouse a separatist line (such as the East Turkistan Liberation Organization, or ETLO) or by unknown perpetrators whom the authors of the document claim, without providing evidence, to be East Turkistan separatists. Moreover, the English version of the document uses the singular form (“the ‘East Turkistan’ terrorist organization”) for terms that in Chinese (which lacks a definite article) are generic and possibly either singular or plural. The document thus implies that there is a unified East Turkistan terrorist organization of considerable strength. From all other indications, however, this is not the case.”

Millward goes on to point out that US government endorsed this sloppiness when it placed the ETIM on the terrorist watch list “thus attributed to ETIM specifically all the violent incidents of the past decade in Xinjiang that the PRC document itself blames only on unnamed groups or on ETLO.” As for the UNRF, the only other source to support the 1,000 trainee claim besides the PRC, Millward notes: “the 80-year-old leader Mukhlisi is now largely discredited and resented by other exile Uyghur groups in Central Asia for exaggerating Uyghur involvement in militant activities—as he did, for example, in March 1997 by announcing that the Urumqi bombings (on the day of Deng Xiaoping’s memorial) were the work of his own and two allied Uyghur groups in Kazakhstan, by all accounts a false claim not even credited by the PRC.”

There is also a question about to what extent the Chinese government attributes what might be criminal acts for financial or other motives. The Yining Riot, also discussed in Millward’s essay, is a clear example. There has never been any evidence submitted that suggests that any sort of terrorist group was involved except PRC allegations that the East Turkestan Islamic Party of Allah provoked it (the ETIPA does not seem to exist beyond this one-off). Dr. Wayne would seem to have failed to differentiate between the claims of the PRC, the UNRF and others, and perpetuated a dangerously oversimplified picture.

Yet despite this commitment of resources and rhetorical energy, Uyghurs across Xinjiang’s social spectrum explain that violent resistance is no longer a viable path. Many Uyghurs in Xinjiang believe that insurgents worsen Uyghurs’ plight by making the Chinese more fearful, thereby more repressive.

This is, in my opinion, a fair and accurate statement. I would certainly not, however, characterize it as winning “hearts and minds”. This is what people crushed by authoritarian repression and fear say. They respond out of fear of what the PRC would do to them, not out of respect (unless you are someone who believes fear is the only form of respect, as regrettably some American conservatives apparently do). Most importantly, Wayne makes a very large mistake: he conflates the Uyghurs with both Al Qaeda and Iraq. Al Qaeda and Iraqi insurgents are not the same to begin with, and comparing it to the Uyghurs is even worse. The Uyghurs, as Millward points out, have long had ethnic nationalist aspirations, as opposed to religious ideological ones. He states:

“The participants in acts of anti-Chinese resistance and their motivations have been varied. Insofar as there is a common denominator, for the twentieth century this has been Uyghur nationalism—sometimes colored by Islam as a basic part of Uyghur culture but not arising from a desire to create an Islamic state per se.”

And this is precisely why Al Qaeda is not a good model for considering Uyghur terrorism, such as it is, and especially inappropriate for judging the views of Uyghurs who do not support violent or ideological means. Uyghurs overwhelmingly harbor nationalist dreams connected most intimately to Turkey, not the Arab states. Pan-Turkicism is an ethnic phenomenon that goes against Al Qaeda’s most basic beliefs. Islam has usually taken the role of garnish, not main dish. Millward then goes on to explain why it’s so tempting to look at Xinjiang through an Islam-centric lens:

“Despite this ethnonationalist, as opposed to religious, basis to Uyghur separatism in Xinjiang, journalists seem to take interest in Xinjiang primarily because it is a majority Muslim area. The reasons for this are clear. I myself once cowrote a magazine article titled “Why Islam Troubles China Too,” capitalizing on the fact, startling and intriguing to a general readership, that China has a large Muslim population in Xinjiang. This fact serves as a perennial hook for pieces about Xinjiang and the Uyghurs, one that seems even more compelling in the aftermat of the 2001 terrorist attacks in the United States, because it fits Xinjiang into the ongoing global narrative of “Islamic terror.” Since stories about Xinjiang usually appear as sporadic features, rather than part of continuing coverage, journalists return to this hook repeatedly with each piece about the region.”

This is part of what I consider the Xinjiang strain of “I Can’t Believe It’s Not China!” journalism.

Why Uyghurs have not radicalized in large numbers is a matter of debate, but certainly one reason is they have not been given the chance – and this is because of China’s strict control that Dr. Wayne claims has been relaxed in exchange for “soft power”. While the PRC may have eased on mass arrests or excessive force, they have not relaxed when it comes to strictly policing religion and free speech. When imams are trained by the state and surveilled, it makes it quite difficult for one of them to preach an extremist message. On the other hand, it makes it impossible for anyone to engage in civil society building or public debate. Dr. Wayne clearly understands this: “The Chinese government purged separatist sympathizers from local governments and attempted to remove political dissent from religious worship“, yet seems to believe that this control has somehow slackened. It has not, just has similar control has not slackened for any other part of the PRC (though it may be more rigid in Xinjiang).

At the same time, availability of Uyghur language education was broadened and Beijing sought to expand economic development in Xinjiang, which was viewed as the key to success.

Dr. Wayne seems unaware of the growing pressure for Uyghurs to study in Chinese language schools. He also continues on about Zawahiri’s message, which mentioned Xinjiang briefly in a list including Chechnya and Spain. He also spent several paragraphs talking about Palestine, but Al Qaeda has yet to show a very strong presence in the Territories. In fact, Hamas has told him to please go away. Another melodramatic bit of flair Wayne uses is to claim “Local men who traveled to Afghanistan to fight the Soviets returned home with new skills and attempted to ply their trade. Young Uyghurs were inspired by the power of men, armed with Allah and AK-47s, to defeat a superpower.” A number of Uyghurs, however, fought on the Soviet side

. I met one in Urumqi who had a Russian tank tattooed on his chest – because he was in one. He was part of the large exodus of Uyghurs to Soviet Central Asia who eventually returned after the 80s.

The raid in Xinjiang upon a group taking mining explosives and building IEDs represents a threat similar to the attacks of Madrid and London: home-grown individuals, radicalizing, building weapons with supplies at-hand.

This sort of blurring of distinctions is precisely one of the biggest problems with the “War on Terror”. To compare angry young immigrant populations inspired by extremists zealots to an angry indigeneous population demanding political freedom is to miss the very key elements necessary to understanding what is going on.

The contrast between China’s project in Xinjiang and U.S.’s actions in Iraq is stark: where China realized that local politics was a key factor for strategic effectiveness, the U.S. has focused on targeting an ever-growing pool of insurgents and terrorists. China’s ultimate success in frustrating al Qaeda’s designs on Xinjiang rests upon its recognizing and responding to the political nature of the threat.

And so we come to Iraq, and here is the biggest failure to make a distinction I could possibly imagine. On the one hand we have China’s “project in Xinjiang”, which is to maintain control over an internal province so as to permanently keep it within their borders under an authoritarian government. On the other hand we have America’s “actions in Iraq”, where the goal, ostensibly, is to leave after establishing a democratic, self-governed nation. China’s efforts in Xinjiang have to been to prevent any kind of unified social movement, whether it be Rebiya Kadeer’s peaceful one or Hasan Mahsum violent one, so that society is organized by Beijing, not the public. If the U.S. wants to make Iraq into a repressive version of Puerto Rico, then Dr. Wayne is right – there are lessons to learn from the PRC.

OK, OK, back to more fun stuff.

Hot Chinese Chicks Brought to You by Pope Gregory XIII

According to Wired News, February 24th marked the 425th anniversary of the Papal Bull institutionalizing the Gregorian Calendar (is that the Gregorian 24th or the Julian 24th?). And in an epic story involving missionaries, Ming, Manchus, merchants, modernizers and hot mamas, it reached China 340 years later. While this might sound awful long, they beat Russia by six years, when the Council of People’s Commissars declared that January 31st would be followed by Valentine’s Day, February 14th. And besides, what’s so great about Pope Gregory?

China did not officially adopt the Gregorian calendar until January 1, 1912, with the founding of the Republic of China, and disposed of traditional Chinese lunar dates. It did not, however, catch on immediately. As Henrietta Hudson points out in her book The Making of the Republican Citizen: Political Ceremonies and Symbols in China, 1911-1929, “Since the government had lost the monopoly the Qing Dynasty had to some extent maintained over the production of almanacs, private publishers suited everyone’s convenience by providing almanacs which listed lunar equivalents of the solar dates and other useful information. Interestingly it seems to have been common for privately published almanacs illegally to claim official authorization.” As a result the government issued a calendar incorporating both in 1914. Use of the Gregorian calendar was a public marker of both political and social revolution, along with such other radical changes such as suits, hats, trousers, skirts, leather shoes bowing to greet someone and polite women appearing in public spaces. The ROC calendar labeled 1912 the Year 1, and continues to be used in Taiwan where it is currently the Year 96, despite pressure last year to abandon it.

China did not officially adopt the Gregorian calendar until January 1, 1912, with the founding of the Republic of China, and disposed of traditional Chinese lunar dates. It did not, however, catch on immediately. As Henrietta Hudson points out in her book The Making of the Republican Citizen: Political Ceremonies and Symbols in China, 1911-1929, “Since the government had lost the monopoly the Qing Dynasty had to some extent maintained over the production of almanacs, private publishers suited everyone’s convenience by providing almanacs which listed lunar equivalents of the solar dates and other useful information. Interestingly it seems to have been common for privately published almanacs illegally to claim official authorization.” As a result the government issued a calendar incorporating both in 1914. Use of the Gregorian calendar was a public marker of both political and social revolution, along with such other radical changes such as suits, hats, trousers, skirts, leather shoes bowing to greet someone and polite women appearing in public spaces. The ROC calendar labeled 1912 the Year 1, and continues to be used in Taiwan where it is currently the Year 96, despite pressure last year to abandon it.

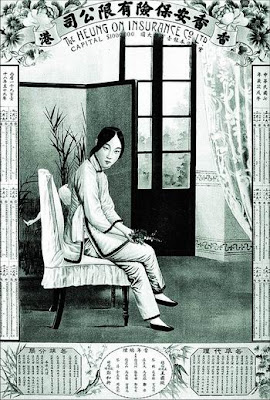

Nothing quite says it all like the Republican era “Shanghai Calendar Girls”, or 月份牌 (yuefenpai). Commissioned often by foreign companies, particularly cigarette manufacturers, and drawn by local Chinese artists, yuefenpai are still strongly associated with Chinese women and Shanghai in particular. Grand pianos, European furniture, sexy women and quite often no calendar (who cares what day it is?), the yuefenpai were the clash of civilizations made into a pin-up.

Some of the more discreet Calendar Girls. The one on the left is from 1918, while the one on the right is not clearly dated. Note the background, hairstyle, and jewelry. This is a modern lady. On the left, too; she’s wearing pants.

Some of the more discreet Calendar Girls. The one on the left is from 1918, while the one on the right is not clearly dated. Note the background, hairstyle, and jewelry. This is a modern lady. On the left, too; she’s wearing pants.

Then there were the other calendar girls. The ones with no calendars. You can view some racier ones here (naughty nude 狐狸精, not quite work-safe), but I like this one for the Art Deco meets Qing look:

The yuefenpai style was later appropriated to some extent by the Communist Party, and taken even farther from being calendars (see Stefan Landsberger’s Iron Women, Foxy Ladies). After using the female image to sell the revolution, it eventually came back full circle when Jin Meisheng, who had painted yuefenpai since 1920 (and did this particularly naughty one involving a dog), published a new (conservative) one in 1989 after decades of painting women revolutionaries.

The yuefenpai style was later appropriated to some extent by the Communist Party, and taken even farther from being calendars (see Stefan Landsberger’s Iron Women, Foxy Ladies). After using the female image to sell the revolution, it eventually came back full circle when Jin Meisheng, who had painted yuefenpai since 1920 (and did this particularly naughty one involving a dog), published a new (conservative) one in 1989 after decades of painting women revolutionaries.

Stayed tuned for Part Two: Is That an Armillary Sphere In Your Robe or Are You Just Happy to See Me?

Hot Chinese Chicks Brought to You by Pope Gregory XIII

According to Wired News, February 24th marked the 425th anniversary of the Papal Bull institutionalizing the Gregorian Calendar (is that the Gregorian 24th or the Julian 24th?). And in an epic story involving missionaries, Ming, Manchus, merchants, modernizers and hot mamas, it reached China 340 years later. While this might sound awful long, they beat Russia by six years, when the Council of People’s Commissars declared that January 31st would be followed by Valentine’s Day, February 14th. And besides, what’s so great about Pope Gregory?

China did not officially adopt the Gregorian calendar until January 1, 1912, with the founding of the Republic of China, and disposed of traditional Chinese lunar dates. It did not, however, catch on immediately. As Henrietta Hudson points out in her book The Making of the Republican Citizen: Political Ceremonies and Symbols in China, 1911-1929, “Since the government had lost the monopoly the Qing Dynasty had to some extent maintained over the production of almanacs, private publishers suited everyone’s convenience by providing almanacs which listed lunar equivalents of the solar dates and other useful information. Interestingly it seems to have been common for privately published almanacs illegally to claim official authorization.” As a result the government issued a calendar incorporating both in 1914. Use of the Gregorian calendar was a public marker of both political and social revolution, along with such other radical changes such as suits, hats, trousers, skirts, leather shoes bowing to greet someone and polite women appearing in public spaces. The ROC calendar labeled 1912 the Year 1, and continues to be used in Taiwan where it is currently the Year 96, despite pressure last year to abandon it.

China did not officially adopt the Gregorian calendar until January 1, 1912, with the founding of the Republic of China, and disposed of traditional Chinese lunar dates. It did not, however, catch on immediately. As Henrietta Hudson points out in her book The Making of the Republican Citizen: Political Ceremonies and Symbols in China, 1911-1929, “Since the government had lost the monopoly the Qing Dynasty had to some extent maintained over the production of almanacs, private publishers suited everyone’s convenience by providing almanacs which listed lunar equivalents of the solar dates and other useful information. Interestingly it seems to have been common for privately published almanacs illegally to claim official authorization.” As a result the government issued a calendar incorporating both in 1914. Use of the Gregorian calendar was a public marker of both political and social revolution, along with such other radical changes such as suits, hats, trousers, skirts, leather shoes bowing to greet someone and polite women appearing in public spaces. The ROC calendar labeled 1912 the Year 1, and continues to be used in Taiwan where it is currently the Year 96, despite pressure last year to abandon it.

Nothing quite says it all like the Republican era “Shanghai Calendar Girls”, or 月份牌 (yuefenpai). Commissioned often by foreign companies, particularly cigarette manufacturers, and drawn by local Chinese artists, yuefenpai are still strongly associated with Chinese women and Shanghai in particular. Grand pianos, European furniture, sexy women and quite often no calendar (who cares what day it is?), the yuefenpai were the clash of civilizations made into a pin-up.

Some of the more discreet Calendar Girls. The one on the left is from 1918, while the one on the right is not clearly dated. Note the background, hairstyle, and jewelry. This is a modern lady. On the left, too; she’s wearing pants.

Some of the more discreet Calendar Girls. The one on the left is from 1918, while the one on the right is not clearly dated. Note the background, hairstyle, and jewelry. This is a modern lady. On the left, too; she’s wearing pants.

Then there were the other calendar girls. The ones with no calendars. You can view some racier ones here (naughty nude 狐狸精, not quite work-safe), but I like this one for the Art Deco meets Qing look:

The yuefenpai style was later appropriated to some extent by the Communist Party, and taken even farther from being calendars (see Stefan Landsberger’s Iron Women, Foxy Ladies). After using the female image to sell the revolution, it eventually came back full circle when Jin Meisheng, who had painted yuefenpai since 1920 (and did this particularly naughty one involving a dog), published a new (conservative) one in 1989 after decades of painting women revolutionaries.

The yuefenpai style was later appropriated to some extent by the Communist Party, and taken even farther from being calendars (see Stefan Landsberger’s Iron Women, Foxy Ladies). After using the female image to sell the revolution, it eventually came back full circle when Jin Meisheng, who had painted yuefenpai since 1920 (and did this particularly naughty one involving a dog), published a new (conservative) one in 1989 after decades of painting women revolutionaries.

Stayed tuned for Part Two: Is That an Armillary Sphere In Your Robe or Are You Just Happy to See Me?

China Missing Out on Overcharging Hipsters

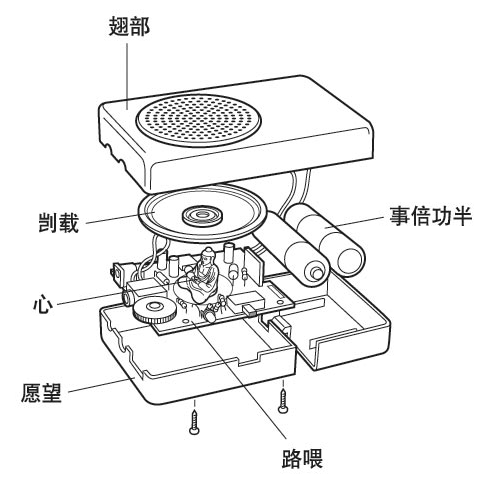

Flickr image courtesy of Merlin @ 43Folders

Flickr image courtesy of Merlin @ 43Folders

In 2005, inspired by the small music boxes used to play Buddhist chants at temples in China, Christiaan Virant and Zhang Jian, collectively known as Beijing’s electronic music group FM3, had 500 little boxes with 9 looping samples of their music made and sold them through boutique outlets for $23 a pop. Thanks to the interest of fellow artists like Brian Eno, the Buddha Machine got a jumpstart and by November it was a gift idea in the New York Times. Hardly more than a year later, there’s been a remix album, a flickr page for devotees, t-shirts, lapel pins, and a mashup game using multiple Buddha Machines (see the demonstration film on YouTube). Now the creators are debuting a porcelain model, with a mythical back story about the Emperor’s Buddha Machine. According to Virant, they’ve sold over 20,000 Buddha Machines and it’s still going strong…

Buddha Machine versus its Grandpa, courtesy of PotatoPotato

Buddha Machine versus its Grandpa, courtesy of PotatoPotato

Dubbed the anti-iPod because of its passing similarity, meagre selection, low-tech capability and of course suggestion of the Buddhist rejection of the material, the Buddha Machine taps perfectly into that “anti-marketing” dollar Bill Hicks used to talk about. The collective Chinese reaction, from those who have heard of it, seems to be a collective “huh”(Chinese), followed by a “wait, $23????” Considering that the real Buddhist chant players can be picked up for far less than a dollar online, it’s hard to argue with that.

There’s two issues here worth noting: Westerners are paying alot of money for something being merchandized as Buddhist, and the difficulties that Chinese companies face in exploiting these kinds of opportunities. One issue is the cultural difference – the “anti-iPod” hook may not be so obvious to a Chinese company, since the iPod does not have the quite the same impact in China as elsewhere. Another problem is that Chinese manufacturing tends not to look favorably on small orders, for high-priced boutique items or otherwise. As Christiaan Variant mentions in an interview at BoomKat:

“This is China, where factories usually take orders in the range of 100,000 to a few million! So when we wanted to make 500, no one would deal with us. Most factories tried to convince us that our idea was pointless or would never sell. But we persisted, did a lot of explaining, pleading and ego-massaging, and eventually one factory took on the task. Now, of course, they are really into the product and just can’t believe it has been so successful.”

Another issue is technical capability. Though China (particularly Dehua, Fujian, near Mutant Palm HQ) has an enormous amount of porcelain manufacturers, FM3 couldn’t make it there:

“Instead, we had factory managers at China’s biggest kilns tell us our plan was “impossible.” Others told us that it was “beyond the realm of modern technology” to copy our humble little plastic box. We were told to seek out the industrial porcelain plants in Japan or Germany – the “only places on the planet” where they had the knowledge to copy a Buddha Machine.”

And so the porcelain model was made in Berlin. China is not, it turns out, the best at making… china.

Chinese literate readers will note, as well, that the assembly diagram at the top of this post has some very strange Chinese words. 心 and 愿望 seem fine and appropriate, but 路喂,翅部,剀载,事倍功半? Well, it turns out that it was made by a Swiss designer who doesn’t know Chinese. But it does looks snazzy.

You can download and listen to uncompressed WAV files of the samples here.

China Missing Out on Overcharging Hipsters

Flickr image courtesy of Merlin @ 43Folders

Flickr image courtesy of Merlin @ 43Folders

In 2005, inspired by the small music boxes used to play Buddhist chants at temples in China, Christiaan Virant and Zhang Jian, collectively known as Beijing’s electronic music group FM3, had 500 little boxes with 9 looping samples of their music made and sold them through boutique outlets for $23 a pop. Thanks to the interest of fellow artists like Brian Eno, the Buddha Machine got a jumpstart and by November it was a gift idea in the New York Times. Hardly more than a year later, there’s been a remix album, a flickr page for devotees, t-shirts, lapel pins, and a mashup game using multiple Buddha Machines (see the demonstration film on YouTube). Now the creators are debuting a porcelain model, with a mythical back story about the Emperor’s Buddha Machine. According to Virant, they’ve sold over 20,000 Buddha Machines and it’s still going strong…

Buddha Machine versus its Grandpa, courtesy of PotatoPotato

Buddha Machine versus its Grandpa, courtesy of PotatoPotato

Dubbed the anti-iPod because of its passing similarity, meagre selection, low-tech capability and of course suggestion of the Buddhist rejection of the material, the Buddha Machine taps perfectly into that “anti-marketing” dollar Bill Hicks used to talk about. The collective Chinese reaction, from those who have heard of it, seems to be a collective “huh”(Chinese), followed by a “wait, $23????” Considering that the real Buddhist chant players can be picked up for far less than a dollar online, it’s hard to argue with that.

There’s two issues here worth noting: Westerners are paying alot of money for something being merchandized as Buddhist, and the difficulties that Chinese companies face in exploiting these kinds of opportunities. One issue is the cultural difference – the “anti-iPod” hook may not be so obvious to a Chinese company, since the iPod does not have the quite the same impact in China as elsewhere. Another problem is that Chinese manufacturing tends not to look favorably on small orders, for high-priced boutique items or otherwise. As Christiaan Variant mentions in an interview at BoomKat:

“This is China, where factories usually take orders in the range of 100,000 to a few million! So when we wanted to make 500, no one would deal with us. Most factories tried to convince us that our idea was pointless or would never sell. But we persisted, did a lot of explaining, pleading and ego-massaging, and eventually one factory took on the task. Now, of course, they are really into the product and just can’t believe it has been so successful.”

Another issue is technical capability. Though China (particularly Dehua, Fujian, near Mutant Palm HQ) has an enormous amount of porcelain manufacturers, FM3 couldn’t make it there:

“Instead, we had factory managers at China’s biggest kilns tell us our plan was “impossible.” Others told us that it was “beyond the realm of modern technology” to copy our humble little plastic box. We were told to seek out the industrial porcelain plants in Japan or Germany – the “only places on the planet” where they had the knowledge to copy a Buddha Machine.”

And so the porcelain model was made in Berlin. China is not, it turns out, the best at making… china.

Chinese literate readers will note, as well, that the assembly diagram at the top of this post has some very strange Chinese words. 心 and 愿望 seem fine and appropriate, but 路喂,翅部,剀载,事倍功半? Well, it turns out that it was made by a Swiss designer who doesn’t know Chinese. But it does looks snazzy.

You can download and listen to uncompressed WAV files of the samples here.

Mass Drivers at Beijing University

“Wenjiang Yang and his colleagues from the Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics and the Chinese Academy of Sciences have investigated the possibility of the “Maglifter,” a maglev launch assist vehicle originally proposed in the 1980s. In this system, a spaceship would be magnetically levitated over a track and accelerated up an incline, lifting off when it reaches a velocity of 1,000 km/hr (620 miles/hr). The main cost-saving areas would come from reduced fuel consumption and the reduced mass of the spaceship. “

“Wenjiang Yang and his colleagues from the Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics and the Chinese Academy of Sciences have investigated the possibility of the “Maglifter,” a maglev launch assist vehicle originally proposed in the 1980s. In this system, a spaceship would be magnetically levitated over a track and accelerated up an incline, lifting off when it reaches a velocity of 1,000 km/hr (620 miles/hr). The main cost-saving areas would come from reduced fuel consumption and the reduced mass of the spaceship. “

physorg (h/t Futurismic)

NASA was examining the feasibility of maglev launchers a few years ago, but it is unclear whether funding has continued. Meanwhile, the US Navy has been using the same technology for a rail gun.

Mass Drivers at Beijing University

“Wenjiang Yang and his colleagues from the Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics and the Chinese Academy of Sciences have investigated the possibility of the “Maglifter,” a maglev launch assist vehicle originally proposed in the 1980s. In this system, a spaceship would be magnetically levitated over a track and accelerated up an incline, lifting off when it reaches a velocity of 1,000 km/hr (620 miles/hr). The main cost-saving areas would come from reduced fuel consumption and the reduced mass of the spaceship. “

“Wenjiang Yang and his colleagues from the Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics and the Chinese Academy of Sciences have investigated the possibility of the “Maglifter,” a maglev launch assist vehicle originally proposed in the 1980s. In this system, a spaceship would be magnetically levitated over a track and accelerated up an incline, lifting off when it reaches a velocity of 1,000 km/hr (620 miles/hr). The main cost-saving areas would come from reduced fuel consumption and the reduced mass of the spaceship. “

physorg (h/t Futurismic)

NASA was examining the feasibility of maglev launchers a few years ago, but it is unclear whether funding has continued. Meanwhile, the US Navy has been using the same technology for a rail gun.