I’ve been more or less out of commission for the past few weeks, as the real world has been keeping me busy. So I missed the Coolest Nailhouse Spectacular that went on in the China blogosphere. But it’s interesting to see how the story evolved from a eye-catching photo in the Oddly Enough section to a narrative about people power, the path from a photo on a Chinese BBS to the International Herald Tribune. What follows is an attempt to piece together an incomplete sketch of how the narrative evolved.

I’ve been more or less out of commission for the past few weeks, as the real world has been keeping me busy. So I missed the Coolest Nailhouse Spectacular that went on in the China blogosphere. But it’s interesting to see how the story evolved from a eye-catching photo in the Oddly Enough section to a narrative about people power, the path from a photo on a Chinese BBS to the International Herald Tribune. What follows is an attempt to piece together an incomplete sketch of how the narrative evolved.

The photo of the nailhouse first appeared, according to Southern Metropolitan Daily, on February 26th (see Peering into the Interior for the translation, March 8th). A picture is apparently worth much more than a thousand words, since it went viral in China and generated far more comments and reposts than a thousand, to the point where SMD picked it up. Then Ananova had it, which got picked up by BoingBoing on March 12th (h/t UGOTrade). That got things rolling in the English speaking Internetz. The Southern Metropolitan Daily had this to say about the holdouts who refused to let a major developer run them out of their house without proper compensation:

“The leaser wanted 200,000,000RMB from the developer or else he wouldn’t move. His family had some background and connections, so the developer didn’t dare take action.”

This, it would turn out, wasn’t true. At the time, from SMD’s sample quotes from the forums, not many people online did either. But the picture was super cool and grabbed eyeballs, all in the shadow of China’s property reform law. That, and China’s own version of eminent domain was a long simmering issue across the nation.

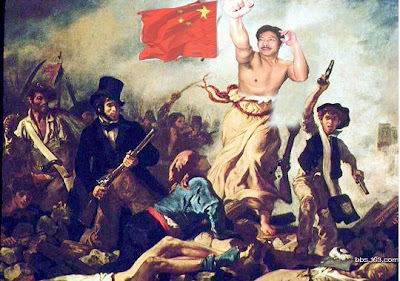

So what happens next? Well, over the next week, journalists flocked to Chongqing and the boards buzzed. The deadline was March 22nd for demolition, creating the perfect air of suspense for “breaking news” coverage. Rumors flew about: Wu Ping and her husband Yang Wu, the tenants, had mafia connections; they wanted 20 million, 4 million, an apartment. Wu Ping herself even confused things; according to Southern Weekend (translation @ ESWN), she claimed her father was a prosecutor and her parents both cadres in the Communist Party. Yet files the paper obtained indicate her father was a Kuomintang soldier and an animal breeder, the former being a bad start to Party membership and the latter being, well, not a prosecutor. Meanwhile, the Internet started cranking out over-the-top deifying Photoshop work of Yang Wu, who was all too made-for-Chinese-media as a former Kung Fu champion defiantly sneaking into the Nail House on the last day before demolition to wave the Chinese flag from the roof, neatly wrapping up nationalism, populism and something out of a Jet Li movie all in one.

Wu Ping even started, for only one post, a Nail House blog the day of the deadline. Two days later, the State Council Information Office put a blackout on Nail House coverage. This was, of course, after Sina.com had been offering cash for photos and videos, MOP.com had real time monitoring, and didn’t stop the subsequent production of a music video (see CDTs’ Nail House coverage), not to mention Wu Ping getting interviewed on the CCTV program Legal Society (see Peering into the Interior again). Neither did it stop the adventurous Zola from becoming what some have dubbed China’s first citizen journalist. Less than four days later, the ban was lifted, presumably after the SCIO realized they weren’t accomplishing anything and were even more ham-fisted than they usually are.

The Nail House wasn’t demolished on the deadline. In fact, it was demolished nearly two weeks later, after the developers and the tenants reached a compromise. The compromise was this (ESWN):

The Settlement Terms for the Chongqing Nail House

According to the Jiulongpo People’s Court, the two-storey building was valuated at 2.47 million RMB while the real estate developer offered a replacement shop/home building valuated at 3.06 RMB; as a result, the house owners Yang/Wu will pay back the difference of 590,000 RMB to the developer.

Furthermore, the real estate develop will pay compensation to the amount of 900,000 RMB for business losses plus 105,000 RMB for property damage and moving expenses. This is coming down from the 5 million plus RMB originally demanded by Yang/Wu.

Did the tenants win what they were after? The Nail House battle didn’t start in February 2007 – it started three years earlier, and that was eleven years after the original developer gave the area residents notice of a land requisition. That developer, Chongqing Nanlong, didn’t have the cash to do anything in 1993 until it partnered with Chongqing Zhengsheng, a state-owned company whose leaders have ties to the local government and local Communist Party. Then, in 2004, residents were offered what most thought was a bad deal, and everybody else took it. Under existing regulations, two forms of compensation could be offered: property of equivalent value in the new development, or cash. Wu Ping and her husband fought for the first option, and for a fair reckoning of the Nail House’s value, a property that was ““First floor for first floor, second floor for second floor. Same direction. Either left or right is okay”, plus compensation for lost business from 1993 to 2006 totalling 5,147,400 RMB. With a property value estimate of 2,470,000 RMB, this put it at nearly 8 million RMB altogether. The courts pushed back the demolition date three times, and there were three negotiations between September 14, 2006 and February 9, 2007. By the third negotiation, the developer had offered a house more or less meeting Wu Ping’s criteria (two floors, on the street, same square area), plus monetary compensation which matched the 700,000 RMB Wu Ping would pay to meet the value of the new property. This is a deal that would net Wu and Yang roughly a 3.2 million yuan property in the location they wanted.

Then another issue cropped up: chops. Wu Ping insisted that Nanlong, the original company that acquired the development rights, place its seal on the agreement. She refused the Zhengsheng seal saying it would not stand up as evidence in court if they tried to pull a fast one on her. She also refused to sign when Nanlong’s legal rep sent his daughter to collect the seal “You can get a seal made anywhere in the street. Why should I believe that this is authentic?”

With the final settlement, questions remain. In the end they are walking away with the property from the February 9th settlement, more or less, and half a million in cash. Was the seal argument just a bargaining tactic to squeeze that little bit more? Was the three year stalemate before the hullabaloo due more to Wu Ping’s apparent savvy, or the Chongqing government’s patience? Do we consider it a win if Wu Ping and Yang Wu haven’t really received compensation for lost business, or being shut out of their own property by the developers? What about the largest issue of collusion between the state and developers? And when 1 out of 280 households chooses to play hardball, can anyone really say there’s a large move towards asserting legal rights? While this has been tied to the new property law in several publications, is it the law, or the media attention drawn to the Nail House by the serendipitous coincidence that the demolition deadline came on the heels of the NPC sessions? As one Chinese commenter pointed out:

China has never had a lack of laws, what it lacks is enforcement. If people are not equal before the law, how effective can this kind of law be?!

Were the laws properly followed in the Nail House case? If Wu Ping truly did use “connections” to simply get access to the courthouse and other government buildings, and needed it, what sort of enforcement could there be, and how could this case possibly increase the possibility of such enforcement? If anything, one could argue the new property law becomes simply one more decree from Beijing for local oligarchs to ignore. After all, it appears all of them in Chongqing kept there jobs in this “successful resolution”.

I said I’d get to the International Herald Tribune. In my next post, I want to look at Howard French’s opinion piece on the Nail House in the context of what I’ve cobbled together here, and how the story reaches American ears.