ESWN links to an article at Ulaan Batar Post about Mongolian Nazis, whose members espouse “The Chinese are our main enemies as they contaminate Mongolian blood by getting married to Mongolian women, and intend to assimilate Mongolians to Chinese” and “It is for their own good […] A small nation can only survive by keeping its blood pure.” In Xinijang, I did meet a few Uighurs who eventually struck up conversations with me beginning with “What do you think about Hitler?” and had similar views about what was necessary to preserve their people. One Uighur YouTube user has a special place for one of Hitler’s speeches on his account, and I suspect that while a minority viewpoint, the sorts of views I heard in 2004 and Justin Rudelson wrote about in his book Oasis Identities, where he points out that Hitler supported pan-Turkic nationalism to undermine the Soviets in Central Asia, and Xinjiang explorer and scholar Sven Hedin had Nazi sympathies. Turkey has had its share of Hitler idolizing as well, such as when a translation of Mein Kampf flew off the shelves in 2005. It’s not strange that there are people in Inner and Central Asia who are racial nationalists, but it always seems like unintended irony to me that people who would have been fairly low on the Nazi racial totem pole would hold up Hitler as a role model. They’re like Asian versions of Clayton Bigsby, the blind black white supremacist from the Chappelle Show.

Liu Jianhua, Sculptor of the Economic Crisis

Artist Liu Jianhua’s (刘建华) latest gallery showing in Italy at Galleria Continua. “Unreal Scene” (2008) is a model of Shanghai made out of poker chips and dice. Photo by Cinghialino, Flickr Creative Commons. More from this and previous Liu works below. He’s currently a professor of sculpture at Shanghai University.

Continue reading “Liu Jianhua, Sculptor of the Economic Crisis”

‘To Collapse or Not To Collapse’ Is Not The Question

Rebecca Mackinnon has started a public wiki for predictions about China in ’09. The first entry is a post by Daniel Drezner whose blog just migrated to Foreign Policy. Drezner cites the recent Charter ’08 manifesto signed by hundreds of Chinese intellectuals and thousands of netizens, which calls for a new constitution, democratic reform and other extraordinarily ambitious changes. Drezner poses the question:

Question to readers: is 2009 the year that China’s government collapses? Or is it just another year in which there will be a crackdown of a mass uprising? Because those may be the only two options.

I agree with Matthew Stinson who points out in the comments to Drezner:

“The main problem with your thesis is the degree to which Chinese intellectuals can shape the discourse, rouse the public, and force policymakers to engage their ideas, and that degree is almost zero.”

Charter ’08 arguably has had a more significant impact on readers of the New York Review of Books than it has on China. Drezner’s position illustrates pretty well American conventional wisdom on China:

1) That for 20 years the Chinese government has been on its “last chance” with the Chinese people, and if it disappoints them, they will rise up and throw the bums out.

2) That the thousands of “mass incidents” reported around the country are warnings that they will carry out this ultimatum.

3) That it’s not a question of if the government will collapse but when, and that everything revolves around the idea of collapse either being imminent or delayed, but always present.

These assumptions ignore complications such as:

1) That the protests of 1989 were not nationwide, nor were they solely composed of students or calls for democracy. Jeffrey Wasserstrom has explicitly pointed out that the protestors were not the same as those in Eastern Europe which Charter ’08 takes its inspiration.

2) That the “mass incidents” around the country are not connected to any intellectual calls to reform, or directed at wholesale change of the national government. In fact, they are commonly directed at local officials and calls for the national government to come to the rescue.

3) The past twenty years, from a Chinese citizens perspective, were in fact revolutionary, and in general China has had quite a bit of revolution and its not exactly something desired.

Here, then, are my predictions for China in 2009 (or 2010, depending how the financial crisis plays out) in no particular order:

- As U.S. and UK retailers, as well as European ones, continue to cut back and even fail, China’s export model will come under increasing strain. The looming credit card crisis will reduce consumption even further, exacerbating the problem. While China has cash to lend on hand, there are no mechanisms by which it can use it to rescue thousands of small and medium sized manufacturers who operate with little spare cash. The government is attempting to use trade policy to buoy exporters, but this can only go so far if Americans have no money to spend.

- It will be extremely difficult for China to increase domestic consumption, not only as thousands lose jobs and unemployment increases, but also because problems with quality assurance in local brands will intensify as manufacturers cut corners even more to increase their shrinking margins and enforcement and regulation mechanisms are ineffective, or in many cases simply don’t exist. There are also bureaucratic hurdles such as permits and fees for imported equipment currently used solely for exports, though the government could waive this in a pinch.

- There will be increasing dissatisfaction and confrontation, but it will focus on education and healthcare, which have long been regarded as the biggest failures of Opening Up and Reform. Like many protests in the past, these will not call for the overthrow of the government but demand the government take action. Its been two years since President Hu Jintao acknowledged the collapse of the healthcare system, particularly in rural areas, but both healthcare and education have suffered similar problems in urban areas as well. First, there is the problem of rampant petty corruption. Second, and overlapping with the first, is that both have been driven purely by how much an individual can pay, either in bribes or by going to more expensive private schools and hospitals (which were mostly built with taxpayers money by public counterparts). It’s “One Country, Two Systems”, based on how wealthy you are.

The Chinese government seems to be aware of all of this, and has been trying to get a healthcare reform package together along with a social security number system. The last one is a mirror image of the U.S. social security number, which began only for tracking government benefits and later became the de facto ID number for legal and financial purposes. In China, its happened almost precisely the other way around. I expect to see the government making some very big noises about healthcare this year, but I’m not so sure education is being given as much priority. Nevertheless, during these past several golden years, Chinese citizens may have been more likely to grudgingly accept the costs of healthcare and education because they could afford them, or at least saw the promise of one day having enough money to afford them. In lean times, when the prospect of future earnings is dim, people may be less likely to accept the status quo and demand the government fix it. It will be interesting to see if this is linked to criticism of the Chinese government’s investment of foreign currency reserves.

Let 1000 Peasant Robots Bloom

via io9, the imaginative robotic creations of Wu Yulu (吴玉禄):

Rural Robots by Wu Yulu from microwavefest on Vimeo.

Wu Yulu was invited to participate in the Microwave International New Media Arts Festival in Hong Kong, which produced this short video. As the video shows, Wu has been a popular fixture in Chinese media, where he’s invariably referred to as “peasant Wu Yulu”. In one extended interview with Wu, one peasant is quoted as saying “For an ordinary peasant to use his mind, it’s not easy, if you asked me to make [robots] I couldn’t” (就一个普通农民动者脑子,那是不简单,要让我做我不成).Likewise, a Chinese Academy of Sciences researcher says it’s not easy for someone like Wu to create such machines because his “cultural level is not very high” (文化水平也不高). Cultural level (wenhua shuiping) is often used to strictly refer to educational level, but has much broader implications. Someones cultural level can be applied to matters of courtesy and etiquette, such as littering or queueing, and generally how “civilized” they are. Measures of civilizing have roots in Qing scholarly elites and rural/urban distinctions and biases, as well as social Darwinist ideas that influenced Chinese 20th century society. A related concept, suzhi (素质) or “human quality”, also touches on these ideas of lesser and greater levels of civilized citizens, and is a core principle of Chinese educational theory. It’s a hierarchy, where progress is measured in comparison to ideal notions of the scholar, the gentry, the elite, the sophisticate.

The whole world makes similar distinctions between city slickers and country bumpkins, aristocrats and farmers, intellectuals and the illiterate. It does seem more clearly articulated in China, however, both in general speech and in the educational system. But this seems irrelevant to Wu’s work. Wu’s robots are primarily mechanical – they don’t appear to have any technological breakthroughs, but are more like mechanical sculptures. It’s hardly surprising that a peasant would be able to learn how to build machines like this, since mechanical repair is an important skill in any Chinese village. What Wu has accomplished doesn’t really have anything to do with formal schooling, it has to do with practical knowledge, obsession (in building one robot, he burnt his house down) and creativity. In the following video, a visiting foreign reporter observes that had Wu been to university, he would be running China’s space program. But to be creative as Mr. Wu has requires the time and space to tinker, to experiment, to burn your house down once or twice. If he had gone to university, he never would have had a chance to do so. If his “cultural level” was higher, he may have been just another middling technician.

Widespread Myopia and the Chinese Language

At left: eye massage goggles based on Chinese medicine jingluo principles.

From the Shanghaiist, news of a new batch of eye massage exercises for Chinese students to help combat China’s myopia epidemic. Eye massage exercises in China have good pedigree, being based on the meridian (经络) theories of Chinese medicine. The first modern eye massage drills were created in 1963, revised in 1972 and have been in Chinese schools since 1982. 26 years later, the eye massage drills are being revised again, partly to “take in to account” that, unlike the malnourished students of 1972, current students are “overnourished, fat” and eat too many sweets. In that same article, however, Chinese health authorities caution that the eye protection drills (眼保健操) are not an effective treatment for myopia.

Vision problems are extremely common in China. China Daily reports that “In 2002, a study found 27 percent of primary students and 63 percent of high school students were nearsighted, more than double that of three decades ago.” Clearly the eye exercises weren’t enough to combat increasing myopia. Xinhua reported a more recent study estimating 31.7 percent of primary students and 82.7 percent of university students have impaired vision and that excessive eye strain is believed to be responsible for 45% of the problem.

Not only Mainland China, but Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, Japan, Malaysia and Korea all have higher rates myopia, which has suggested a genetic explanation. But even if a genetic factor is involved, there’s lots of evidence that more nearwork (such as reading) and less sports activity correlate to increased myopia. In one study, rates of myopia in Chinese peasants were found to be around 5%, while scholars had nearly 85%. A study in Taiwan found that older Chinese people and older white people had comparable rates of myopia, but younger Chinese had it far more than younger whites. All of this suggests that with increased literacy and reading in China comes myopia.

The Chinese language clearly involves more nearwork than the English written language. A recent post by Chinese blogger Hecaitou provided a great example of this. There’s an English email forward is an “Alzheimer’s Test” that has three questions like this one:

This is a REAL neurological test. Sit comfortably and feel calm.

1- Find the C below. Do not use any cursor help.

OOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO

OOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO

OOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO

OOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO

OOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO

OOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO

OOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOCOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO

OOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO

OOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO

OOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO

OOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO

Hecaitou made a Chinese one:

最后是令人崩溃的中文版…… 请从诸多的“己”中,找出“已”…….

己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己已己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己己

You have to squint just to see the difference between 己 & 已. That’s not exactly the case with O & C, though both searches are difficult.

On a more serious note, consider the differences in this eye tracking study of Google and Baidu users. Note the first image comparing eye tracking heat maps for English Google and Chinese Google:

Here’s one of the explanations the author thought was involved:

Another difference is the way we interact with the information in the listings themselves. In North America, we scan and pick up word patterns. We recognize words quickly and determine if they fit in our “semantic maps” (another term covered in our eye tracking studies), but we don’t read the listings.

Because Chinese is presented as symbols, where concepts take their final meaning from a group of combined symbols, it’s much more difficult to scan this information quickly. To try to put in a Western conceptual framework, imagine how difficult it would be to scan meaning from this paragraph if our alphabet was extended to 2000 characters, presented in block letters and all the spaces between words were removed. I can’t do anything about extending the alphabet, but I can change it to block letters and remove the spaces:

TOTRYTOPUTINAWESTERNCONCEPTUALFRAMEWORK,IMAGINEHOW DIFFICULTITWOULDBETOSCANMEANINGFROMTHISPARAGRAPHIF OURALPHABETWASEXTENDEDTO2000CHARACTERS,PRESENTEDIN BLOCKLETTERSANDALLTHESPACESBETWEENWORDSWEREREMOVED

One can begin to understand why it might be difficult to scan and pick up individual concepts quickly.

Perhaps the incidence of myopia in China would be reduced if text were segmented. I wonder what John DeFrancis would say.

A Tale of Two Stampedes

via Blood & Treasure:

via Blood & Treasure:

An employee at Wal-Mart was killed yesterday when “out-of-control” shoppers broke down the doors at a sale at the discount giant’s store in Long Island, New York.

Other workers were trampled as they tried to rescue the man and at least four other people, including a woman who was eight months pregnant, were taken to hospitals for observation or minor injuries following the incident.

Customers shouted angrily and kept shopping when store officials said they were closing because of the death, police and witnesses said. The store, in Valley Stream on Long Island, closed for several hours before reopening.

Nassau county police said about 2,000 people were gathered outside the store doors at the mall about 20 miles east of Manhattan. The impatient crowd knocked the man, identified by police as Jdimytai Damour,34, of the New York city borough of Queens, to the ground as he opened the doors, leaving a metal portion of the frame crumpled like an accordion.

Shoppers stepped over Damour as he lay on the ground and streamed into the store. When told to leave, they complained that they had been in line since Thursday morning for the Black Friday sale that traditionally follows the Thanksgiving holiday…

…Dozens of store employees trying to fight their way out to help Damour were also trampled by the crowd, the police spokesman added. Items on sale at the store included a Samsung 50-inch plasma high-definition TV for $798 (£520), a Samsung 10.2 megapixel digital camera for $69 and DVDs such as The Incredible Hulk for $9.

Almost exactly one year ago:

Three people died and 31 others were injured in a stampede as shoppers scrambled for cut-price cooking oil at a Carrefour store in China on Saturday, Xinhua news agency reported.

The tragedy came during a promotion to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the founding of the store in Shapingba district in southwest China.

People began queuing in the early hours of Saturday to buy the cooking oil, said Gao Chang, a spokesman for the Shapingba district government. When the shop opened for business, throngs of people burst in and a mass stampede occurred.

Both incidents have prompted soul searching. From the New York Times a title bursting with hyperbole*, A Shopping Guernica Captures the Moment:

In a sense, the American economy has become a kind of piñata — lots of treats in there, but no guarantee that you will get any, making people prone to frenzy and sending some home bruised.

It seemed fitting then, in a tragic way, that the holiday season began with violence fueled by desperation; with a mob making a frantic reach for things they wanted badly, knowing they might go home empty-handed.

From Southern Metropolitan Daily’s less colorfully titled The Social Problems Embedded in 11 Yuan:

However, when people feel that they can benefit more from not following the rules than from following them, then someone who lines up honestly will probably get nothing. Such a reality leads people to ignore the system because the cost of following the rules is too high. Uncertainty about tomorrow makes people trust only what they can see in front of them; they own only what they can get their hands on. Who knows what lies ahead—you might never get that eleven yuan discount if you are just one step too late.

In both cases, domestic pundits are quick to use the stampedes to diagnose greater social ills. In both cases, those social ills include financial security in the face of economic uncertainty. The differences are stark: the Chinese stampede was over a basic food product becoming more expensive due to inflation. The American stampede was over flat screen TVs and holiday gifts in a recession. The Chinese government responded by banning time-limited promotions in supermarkets across the country, while the U.S. will most likely settle it through individual lawsuits.

————————-

* Is the New York Times referring to Guernica the painting, or Guernica the bombing? Either way I find it an asinine comparison.

Golden Oldies of U.S. Propaganda: Red Chinese Battle Plan

Here’s a classic from the old days. Red Chinese Battle Plan was a full throated 1964 U.S. Navy propaganda film about China becoming global Communism’s “Second Rome” after Khrushchev said bad things about Uncle Joe and got sociable with the Americans. Its Chinese history seems a little strange:

This is in the beginning of the film, when the narrator tells us that “never had a major independent nation lost so much sovereignty, or suffered so much humiliation”. It doesn’t say exactly when, and the map doesn’t help. First we see Burma and what appears to be Nepal, Sikkim and Bhutan fall. As far as Wikipedia goes, Burma defeated 4 Qing invasions before falling to the British Raj, while the other three seem to have had their differences with Tibet, which would occasionally call on the Mongols or Qing to help. Even if there were tributes paid by these regions, they were most likely symbolic. It hardly seems fair to say they were Qing territory, and there doesn’t seem to be a particular timeframe for all of them going at once.

Then Xinjiang, Mongolia and Manchuria all seem to go at the same time. These regions were taken piece by piece by Russia, Japan and others, but not all of it (Xinjiang was a total basketcase) and not all at once. Then, weirdly, Korea falls after Manchuria, since the Sino-Japanese War was in 1895 and Russia invaded Outer Manchuria in 1900. The Nguyen regime in Vietnam defeated the Qing army invasion of Hanoi and then paid tribute to the Qing Emperor, but also set things up so officially “it was a child who dealt with Beijing”. Any comments untangling what all that implies are appreciated – Granite Studio? A little help? Sun Bin?

The most interesting bit, though, has to be Tibet staying on the team. Apparently in 1964 the U.S. Navy didn’t agree with the Dalai Lama that Tibet became de facto independent in 1911.

If you ignore the blatant rah-rah American freedom stuff in the movie, it does have periods of being reasonably informative. Then it talks about how Mao Zedong and Lin Biao (that didn’t work out) are going to conquer the world by invading the “rural countries” (Asia, Africa and Latin America) as stepping stones to the “city countries” (the U.S. and Europe):

Chinese communism never really pulled off stage one of this supposed “battle plan”. Chinese capitalism, on the other hand, appears to be making a go of it. Then again, as the Wall Street Journal points out, China’s investment in the U.S. dwarfs that in Latin America. I guess everybody wants to be in the cities these days.

Before Global Voices & The Internet, There was PLATO

There’s an article in Wired about Microsoft’s Chief Software Officer Ray Ozzie, who in the 70s was part of the PLATO project, which inspired him to create Lotus Notes. From Wikipedia: “PLATO was the first (circa 1960, on ILLIAC I) generalized computer assisted instruction system. It was widely used starting in the early 1970s, with more than 1000 terminals worldwide. PLATO was originally built by the University of Illinois and ran in four decades, offering elementary through university coursework to UIUC students, local schools, and more than a dozen universities.” PLATO was bought in 1976 by Control Data Corporation, whose founder William C. Norris believed that PLATO would not only be profitable, but would be able to solve various social ills through computerized education. CDC expanded PLATO across the world. In the 1980s, there was even a PLATO cartridge for the Atari Computer (designed by China-born Vincent Wu) that offered access to “200,000 hours of coursework”.

PLATO had email, IM and group chat in 1973 before there were even BBSes, and perhaps more astonishing, “Any competent PLATO programmer can quickly hack together a simple chat program that lets two users exchange typed one-line messages. PLATO’s architecture makes this trivial.” Funny enough, the “Notes” proto-email program was meant to be a bug reporting system, but ironically a bug, people not talking about bugs, ended up a feature.

Probably the most interesting part so far is this, unfortunately unsourced, section of the Wikipedia entry on PLATO in South Africa:

There were several other installations at educational institutions in South Africa, among them Madadeni College in the Madadeni township just outside of Newcastle.

This was perhaps the most unusual PLATO installation anywhere. Madadeni had about 1,000 students, all of them black and 99.5% of Zulu ancestry. The college was one of 10 teacher preparation institutions in kwaZulu, most of them much smaller. In many ways Madadeni was very primitive. None of the classrooms had electricity and there was only one telephone for the whole college, which one had to crank for several minutes before an operator might come on the line. So an air-conditioned, carpeted room with 16 computer terminals was a stark contrast to the rest of the college. At times the only way a person could communicate with the outside world was through PLATO term-talk.

For many of the Madadeni students, most of whom came from very rural areas, the PLATO terminal was the first time they encountered any kind of electronic technology. (Many of the first year students had never seen a flush toilet before.) There initially was skepticism that these technologically-illiterate students could effectively use PLATO, but those concerns were not borne out. Within an hour or less most students were using the system proficiently, mostly to learn math and science skills, although a lesson that taught keyboarding skills was one of the most popular. A few students even used on-line resources to learn TUTOR, the PLATO programming language, and a few wrote lessons on the system in the Zulu language.

I found some of the sources, though: this section appears to be copied, more or less, from an article by Owen Gaeda, a PLATO developer who taught PLATO in Madadeni Teachers College for two years. Wired has another article from a PLATO reunion in 1997, where it mentions Brian L. Dear has been researching a book called PLATO People since 1985. I hope he finishes it soon. In the meantime, there’s a PLATO emulator system on the Web called Cyber1.

Bonus: The ANC used Commodore 64s to encrypt messages and play them to a tape recorder with an acoustic coupler modem. The receiver would record the playback with another tape recorder over the phone, then play it for their computer. The digital sound of resistance.

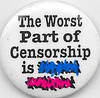

WordPress Plugin To Subvert Chinese Keyword Blocks

Last year, Ryan McLaughlin at DaoByDesign came up with a plugin called Censortive, which replaces sensitive keywords in WordPress blog posts with image equivalents, thereby avoiding keyword blocks like those mentioned in the last post. At the time, though, Chinese language support was problematic. But since then, some good open source Chinese font packages have been developed. Two that work are Wen Quan Yi (文泉驿) and Fireflysung (螢火飛點陣字型). There are a couple of other fonts here that might work as well. Instructions for installing Censortive are here.

Last year, Ryan McLaughlin at DaoByDesign came up with a plugin called Censortive, which replaces sensitive keywords in WordPress blog posts with image equivalents, thereby avoiding keyword blocks like those mentioned in the last post. At the time, though, Chinese language support was problematic. But since then, some good open source Chinese font packages have been developed. Two that work are Wen Quan Yi (文泉驿) and Fireflysung (螢火飛點陣字型). There are a couple of other fonts here that might work as well. Instructions for installing Censortive are here.

The next step, of course, is making the list of keywords. Censortive works by assigning codewords to the words you want to replace, so that the actual words are not present in the html either (otherwise it wouldn’t really work). Unfortunately, that means that spreading a common set of codewords would probably work for a while, but if it were really successful the censors would begin scanning for the codewords. Let ’em.

So we need to make a list. Here’s some places to start gathering words:

- The keyword list to a javascript that several sites host that claims to see how many “banned words” are in a webpage. The list seems a bit suspect, but worth searching in.

- Here’s a Google Doc of the banned words used in the Tom Online version of Skype.

- The ChinaSMACK Internet slang glossary may be useful.

- And here’s the Wikipedia list of censored words.

- This list from Roland Soong seems to still have some oomph after four years.

I would note that only ESWN’s page is blocked (for me), the rest aren’t, though maybe the Google Docs one would be if it weren’t SSL.

So tell all your Chinese blogger friends they can now replace bad words with pictures thanks to this [*nb*] plugin.

Flickr image courtesy of Net Efekt.

Is the Net Nanny’s Aim Improving?

The People’s Security Bureau in Shenzhen has told blogger Zuola couldn’t leave the country to attend the Deutsche Welle Blog Competition (where he would be a judge) because he’s a “may threaten state security” (“可能危害国家安全”). Then his twitter page got blocked by the Net Nanny, along with fellow activist bloggers Amoiist and Wenyunchao. The rest of Twitter remained accessible, and precision Twitter blocks haven’t been seen before*. You can read more about Zuola’s background and what his refused entry might mean over at Rebecca MacKinnon’s blog, which is also blocked, and has been for a while. Or rather, all subdomains of “blogs.com”, which hosts Rebecca’s blog, were blocked for quite a while. Now it’s just her. The same used to be true of all “typepad.com” subdomains. Now it’s just Letters From China that’s blocked, and McClathy newspapers Beijing correspondent Tim Johnson is unscathed. Blogspot was blocked on and off for ages, and is currently available – but not the GFW blog. Even Livejournal is fully available now. I don’t know if anyone is being blocked there, because frankly, it was blocked for so long I don’t think anyone in China still posts there except this guy, who has written about Zuola and the GFW, but perhaps the censors also assumed no one uses Livejournal.

So now at Twitter, Blogspot, Typepad and Blogs.com, blanket blocks have been replaced with precision blocks on blogs with “politically sensitive” content (all the examples above). If the blanket blocks are really going away for good, this is a good thing for three reasons:

1) The government is giving up on carpet blocking whole net neighborhoods, which is pretty heavy handed.

2) It opens up outside blogging platforms that don’t have an in-house censor shop to Chinese users.

3) It may sound weird, but it’s actually a good thing that it targets specific people, because we know who they are. In order to work, censorship has to keep alot of things vague and fuzzy, like what specifically can’t be said, what will happen if you say it, and who is saying it. When whole blog platforms were blocked, it was hard to know why. People often speculated that one blog said something that wasn’t looked favorably upon, and so the whole domain got harmonized. Now we don’t have to guess.

It’s not clear whether the precision blocks are based on keywords or the domain in some cases, but it seems likely that the latest Twitter blocks are not keyword based, simply because alot of people are retweeting Zuola and they aren’t getting blocked. Likewise Letters From China got a personal block a while ago, and there’s good reason to expect Rebecca got one of those.

Now I’d like to mention one of those little mysteries of the Net Nanny that I’d like to solve. For a while now I’ve noticed that quite a very random looking assortment of comic book and scifi related blogs are blocked. They all have their own domains and none seem to have ever had anything to say about China whatsoever. Do the censors have a problem with steampunk, speculative fiction and graphic artists? Or is still more bad aim?

———————————–

*use “https” and you’ll get through. The goes for mutantpalm.org as well. You’ll just have to accept my unvalidated security certificate, because I’m not going to pay for one.

Flickr Image Courtesy of Shizhao.