Matteo Ricci’s Chinese World Map & Kashgari’s Diwan

Via the incomparable Warren Ellis, comes an article on UFOs in The Canadian that caught his attention for this one liner by the author:

Who then was the being whose blond hair inexplicably became wrapped around Peter Khoury’s penis?

Indeed, these are the burning questions of our era. Leave it to the Canadians; former Defence Minister Paul Hellyer claims the world governments secretly possess alien tech that can solve global warming. Peter Khoury is an Australian who claims to have been sexually assaulted by two aliens posing as human women.

One looked somewhat Asian, with straight dark shoulder-length hair and dark eyes. The other looked “perhaps Scandinavian-like”, with light-coloured (“maybe bluish”) eyes and long blond hair that fell half-way down her back.

The Scandinavian-like alien, apparently, tied her hair around Peter’s, um, peter. What’s really interesting about the article is that the story was told by “Bill Chalker at a well-attended Chinese UFO conference, which included Chinese scientists”. That would be the 2005 UFO conference in Dalian. In fact, according to his blog, Bill might have even spotted a UFO during the flight to Dalian.

The China connection goes much, much further. According to The Canadian (from Chalkers book “HAIR of the ALIEN – DNA and other Forensic Evidence of Alien Abduction”, which discusses the Khoury case):

After thorough testing of the hair samples, the scientists of the Anomaly Physical Evidence Group arrived at a startling conclusion. The thin blond hair, which appeared to have come from a light-skinned caucasian-like looking woman, could not have come from a normal human of that racial type.

Instead, though apparently ‘human’, the hair showed five distinctive DNA markers that are characteristic of a rare sub-group of the Chinese Mongoloid racial type. (Ed. – so rare Mongoloids are not “normal humans”?)

A detailed survey of the literature on variations in mitochondrial DNA, comprising tens of thousands of samples, showed only four other people on record with all five of the distinctive markers in the blond hair. All four were Chinese, with black hair.

Mitochondrial DNA is passed only from mother to child and therefore offers a means of tracing ancient ancestry on the mother’s side. The findings suggest that all four of the Chinese subjects share a common female ancestor with the blonde woman. But there is no easy explanation for how this could be.

There is an easy explanation. Several. They’re called Xiongnu, Juan-Juan, Scythians, Sogdians, Orkhon, Kyrgyz, Uyghurs… etc. etc.

“Also, given the Asian mongoloid connection, we looked at the problem of European-like rare Asian types in the past,” Mr. Chalker says. “The controversial saga of the Taklamakan mummies in remote Western China is turning the early history of China on its head. These mummies include people who are quite tall, some 6 feet or so, and some are blond. I’m not suggesting a connection here, but you can understand this investigation has opened up all sorts of interesting possibilities about the biological nature of some of the beings implicated in abduction cases.”

There’s actually some people in China who might jump right on this theory that Turkic people are from outer space. It’s not just one conference in Dalian. Plans for a UFO Museum and Research Center in Guiyang have been underway for a couple of years with Taiwan investors, and Chinese news sites have published such great stories as repeating the myth that Neil Armstrong saw a UFO on the moon

One great example is Zhang Hui (张晖), a researcher at the Xinjiang Museum. Zhang Hui has researched and written two books on the Green River Valley in Ili, Xinjiang: Valley of the Cyclops 《独目人山谷》, and the upcoming Connecting Heaven and Earth: Xinjiang and Alien Civilizations 《通天之地: 新疆与外太空文明》. In this article, Zhang Hui argues that what have generally been considered Scythian burial mounds are, in fact, not only 2500 years older, but match the patterns found for crop circles by the Centre for Crop Circle Studies, a British organization that seems to have lost their webpage (contacts here).

One great example is Zhang Hui (张晖), a researcher at the Xinjiang Museum. Zhang Hui has researched and written two books on the Green River Valley in Ili, Xinjiang: Valley of the Cyclops 《独目人山谷》, and the upcoming Connecting Heaven and Earth: Xinjiang and Alien Civilizations 《通天之地: 新疆与外太空文明》. In this article, Zhang Hui argues that what have generally been considered Scythian burial mounds are, in fact, not only 2500 years older, but match the patterns found for crop circles by the Centre for Crop Circle Studies, a British organization that seems to have lost their webpage (contacts here).

Moreover, Zhang Hui argues that the cave paintings at Tangbalei (唐巴勒) depict the “emissaries of a superior civilization”. Who are cyclopses. (is that the plural of cyclops?)

Moreover, Zhang Hui argues that the cave paintings at Tangbalei (唐巴勒) depict the “emissaries of a superior civilization”. Who are cyclopses. (is that the plural of cyclops?)

Photo courtesy of Steve Cadman of an armillary sphere at the Beijing Observatory, probably a copy of a sphere constructed by Guo Shoujing (1231-1314) in Nanjing.

Photo courtesy of Steve Cadman of an armillary sphere at the Beijing Observatory, probably a copy of a sphere constructed by Guo Shoujing (1231-1314) in Nanjing.

Following up on the previous post about calendars in China (Hot Chinese Chicks Brought to You By Pope Gregory XIII), I thought I’d take a look at the science and art behind Chinese astronomy. Calendars in China have always been of the utmost political, as well as practical, importance. As the Son of Heaven blessed with the Mandate of Heaven, the Emperor needed to be the first and last word on the heavens themselves. When the moon would be full, when an eclipse would occur, these were quite literally matters of life and death. Since China had a lunar calendar, errors were more common than on a solar calendar, and an error could lead to revolution. As Helmer Aslaksen puts it in his paper The Mathematics of the Chinese Calendar, “Every peasant would then on the first day of the month see either a waxing crescent or a waning crescent [instead of a new moon]. Why should they pay taxes and serve in the army if the emperor did not know the secrets of the heavens?” Even worse was if you were a scientist working for the Emperor, as Jesuit missionaries Adam Schall, Ferdinand Verbiest and their Chinese colleagues found out in the “Calendar Case” in the early Qing. Accused of screwing up their calculations (as well as casting a spell on the Emperors parents), they were thrown in jail. To try and defend themselves, they predicted an upcoming eclipse more accurately than the Chinese officials plotting to get them executed. But it wasn’t until an earthquake caused a fire in the Imperial Palace and a comet appeared that the Emperor thought maybe Heaven didn’t want them to die. Even then, the Jesuits Chinese colleagues were still put to death. Ed. – the laowai always get off easy, don’t they?

So obviously alot of creativity and energy went into Chinese astronomy. There was some form of Chinese calendar as far back as the 13th or 14th century BCE, as the oracle bones show a form of dating, albeit an inaccurate one. By 589 BCE, the Chinese had it down to a cyclical correction, the Metonic cycle, one the Greeks and Babylonians would use a century later. The Chinese calendar is a lunisolar calendar, not a lunar one. The Muslim calendar is lunar, the Gregorian is solar, but the Jewish and Chinese calendars are lunisolar, meaning that they try to cram 12 months into a tropical year. Unfortunately, you come up 11 days short, so they needed to stick a leap month in every once and while, which is not easy. As Aslaksen puts it:

So obviously alot of creativity and energy went into Chinese astronomy. There was some form of Chinese calendar as far back as the 13th or 14th century BCE, as the oracle bones show a form of dating, albeit an inaccurate one. By 589 BCE, the Chinese had it down to a cyclical correction, the Metonic cycle, one the Greeks and Babylonians would use a century later. The Chinese calendar is a lunisolar calendar, not a lunar one. The Muslim calendar is lunar, the Gregorian is solar, but the Jewish and Chinese calendars are lunisolar, meaning that they try to cram 12 months into a tropical year. Unfortunately, you come up 11 days short, so they needed to stick a leap month in every once and while, which is not easy. As Aslaksen puts it:

Israel, the religious leaders would determine the date for Passover each spring by seeing if the roads were dry enough for the pilgrims and if the lambs were ready for slaughter. If not, they would add one more month. An aboriginal tribe in Taiwan would go out to sea with lanterns near the new Moon after the twelfth month. If the migratory flying fish appeared, there would be fish for New Year’s dinner. If not, they would wait one month.

The Metonic cycle was later used in both, and added some regularity. It was easier for the Jewish calendar, which, like the Gregorian calendar, is founded on a set of arithmetical rules. The Chinese and Muslim calendars, however, are astronomical. Hence Islamic calendar websites like MoonSighting.com which produces world maps and math jokes, and a Chinese New Year that keeps you guessing (is there a Chinese MoonSighting.com equivalent?)

But before there were satellites or webpages, you had to figure out as precisely as possible what the moon was doing. This isn’t easy – due to the changing speed of the Earth in orbit, the effect of the moon on the Earth, and a whole lot of other factors that I have no clue about, there were alot of problems. One of these tools was the gnomon, which was essentially a stick in the ground, and you measured the shadows of the sun and moon. Anyway, it’s not very exciting. Another was the armillary sphere, as pictured above. You’ve seen it in Harry Potter.

But before there were satellites or webpages, you had to figure out as precisely as possible what the moon was doing. This isn’t easy – due to the changing speed of the Earth in orbit, the effect of the moon on the Earth, and a whole lot of other factors that I have no clue about, there were alot of problems. One of these tools was the gnomon, which was essentially a stick in the ground, and you measured the shadows of the sun and moon. Anyway, it’s not very exciting. Another was the armillary sphere, as pictured above. You’ve seen it in Harry Potter.

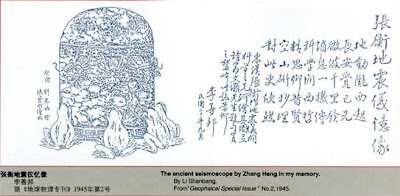

The armillary sphere (浑仪) is ancient, and that’s why you often see it in wizards offices in movies. No one is really sure who made one first, but the Chinese astronomer Zhang Heng 张衡 was probably one of the first. Not only that, but it was water-driven, which would be used again later by Su Song. An armillary sphere basically allows you to find the position of an object in the sky in relation to the celestial equator, (equatorial AS or 赤道经纬仪) or the ecliptic (the path of the sun across the sky) (ecliptical AS or 黄道经纬仪).

The armillary sphere (浑仪) is ancient, and that’s why you often see it in wizards offices in movies. No one is really sure who made one first, but the Chinese astronomer Zhang Heng 张衡 was probably one of the first. Not only that, but it was water-driven, which would be used again later by Su Song. An armillary sphere basically allows you to find the position of an object in the sky in relation to the celestial equator, (equatorial AS or 赤道经纬仪) or the ecliptic (the path of the sun across the sky) (ecliptical AS or 黄道经纬仪).

Zhang Heng is probably better known for his earthquake detector, a giant faberge egg with dragons along the sides holding balls in their mouths. If a ball fell out, there was an earthquake in that direction.

China benefited from a great deal of foreign astronomy as well. In the Tang Dynasty, the Buddhist monk Yi Xing (一行) used the Jiu Zhi Li (九执历) calendar, which was based on an Indian one, to make the Da Yan Li (大衍历). It was at this point the Chinese abandoned the metonic cycle, or an arithmetical rule, to follow the actual movement of the moon with all its eccentricities. In the Yuan Dynasty, Guo Shoujing and others were influenced by the texts of Muslim astronomers, such as Zij (1366) and al-Madkhal fi Sina’at Ahkam al-Nujum [Introduction to Astrology] (1004?). An astrolabe built to Islamic sources specification was installed in Nanjing in 1385. Guo Shoujing managed to create a new form of equatorial armillary sphere, a sort of disassembled one, the equatorial torquetum. The torquetum had a very important improvement: it wasn’t so friggin’ confusing. This is why in Chinese the equatorial sphere is typically referred to as the 浑仪 (literally “muddy apparatus”, and the torquetum is referred to as the 简仪 (“simple apparatus”). Guo Shoujing and his buddies put all this to use and created the Shoushi (授时历) calendar. Pierre Simon de LaPlace, five centuries later, would use some of Guo Shoujing’s observations, along with other ancient Chinese and Muslim sources, to demonstrate the change in obliquity in the ecliptic (the narrowing angle between the ecliptic and the celestial equator).

In 1088, Su Song (苏颂) built a massive water-driven armillary sphere. Joseph Needham described the “Water Clock”, as it is commonly known, as follows:

In 1088, Su Song (苏颂) built a massive water-driven armillary sphere. Joseph Needham described the “Water Clock”, as it is commonly known, as follows:

“surmounted by a huge bronze power-driven armillary sphere for observation, and containing, in a chamber within, an automatically rotated celestial globe with which the observed places of the heavenly bodies could be compared. On the front of the tower was a pagoda structure with five stories, each having a door through which manikins and jacks appeared ringing bells and gongs and holding tablets to indicate the hours and other special times of the day and night. Inside the lower was the motive source, a great scoop-wheel using water and turning all the shafts working the various devices…. One must imagine this giant structure going off at full-cock every quarter of an hour with a great sound of creaking and splashing, clanging and ringing; it must have been impressive….”

Unfortunately, the Jin invaded, took it apart and brought it back to Beijing where they couldn’t put it back together again. Later the Emperor commanded Su Song’s son, Su Xie, to rebuild it. He couldn’t. A scaled down replica is on display at Taiwan’s National Museum of Natural Science, and a 1:48 model is at the British Science Museum.

Unfortunately, the Jin invaded, took it apart and brought it back to Beijing where they couldn’t put it back together again. Later the Emperor commanded Su Song’s son, Su Xie, to rebuild it. He couldn’t. A scaled down replica is on display at Taiwan’s National Museum of Natural Science, and a 1:48 model is at the British Science Museum.

One other interesting character who contributed to the study of astronomy and calendars was Huang Daozhou (黄道周), who would later assist Prince Tang in Fuzhou against the invading Manchus of the soon-to-be Qing Dynasty. Like all of these scholars, he was a philosopher, a scientist, political figure and artist. I like this image because of hexagrams alongside the constellations:

And then there were the Jesuits, who made some cool looking stuff. These are from the Ibiblio Vatican collection. In order, these are Matteo Ricci’s explanation of astronomy, Adam Schall van Bell’s star chart, and Ferdinand Verbiest’s strange forays into the I-Ching. Three generations of missionaries:

And then there were the Jesuits, who made some cool looking stuff. These are from the Ibiblio Vatican collection. In order, these are Matteo Ricci’s explanation of astronomy, Adam Schall van Bell’s star chart, and Ferdinand Verbiest’s strange forays into the I-Ching. Three generations of missionaries:

Noah Shachtman caught this story from Flight Global over at Wired’s Danger Room blog:

German-headquartered SIM Security and Electronic System says it has sold an undisclosed number of its Sky-Eye quadrotor UAVs into China for use by a civilian police organisation. Total sales of the existing system, including the Chinese orders, have exceeded 30 units according to Yves Degroote, Brussels account manager for the firm.

Noah says:

Sales of drones are tightly controlled by the International Traffic in Arms Regulations, or ITAR. Companies usually have to get special clearance to market the things — even in friendly countries. I’m no ITAR expert, but I believe sales to countries like China are even more carefully monitored. About a year ago, officials at Yamaha in Japan were busted for shipping nine robo-copters to the Beijing regime.

Does anybody have any idea how you say “quadrotor UAV” in Chinese? Or would these just be called 天眼 after the brand name?

UPDATE: It’s China time in the Danger Room as Sharon Weinberger points to an English People’s Daily article on Chinese scientists success at controlling the flight of pigeons with brain implants. But they don’t have a picture, so I’ll help by adding the Chinese article.

Since China is rather short on pigeons (at least not in cages), obviously these are for overseas operations. The robocoptor won’t be noticed on the streets of Shanghai, but free flying pigeons would probably surprise the hell out of people. Check out the Shangdong Science and Technology University Robot Research Center website for things like the Electrical Powerline Repair Robotic Arms and other stuff that, so far, is nowhere near as cool or gross as a pigeon with a chip in its skull.

Back in 2004, a news surfaced about CCTV producing it’s first ever science fiction TV show, Angel Online (天使在线). Sina.com.cn had a whole page devoted to it, complete with quote from the director and Chinese scifi writers talking about the need for science fiction in encouraging creativity, and how this would be China’s Star Wars, Matrix and Heat Vision and Jack rolled into one. (You can read a synopsis here, in which artificial intelligence “Net Babies” (网婴) become all the rage, only for one becomes all-powerful on the Internet). And then it became impossible to find anymore news about it – and not only because 天使在线 is the name of a popular MMO gaming webpage. Then I noticed that Seed Magazine’s China Science section mentioned it last September, and I figured I’d check Baidu again. Turns out in January Sina reported that Jackie Chan might join the show?!?? I’ll believe it when I see it, since in 2004 principal photography was suppose to start in 2005 and now Sina says it’ll be out in 2008. But in the mean time, it turns out a major fan has been working on a Chinese machinima movie: 原始地带 ZONE OF BARBARISM! You can watch a short confusing clip here, which consists of helicopter animations, the back of a head that could be Chuck Norris, and a gorilla. Perhaps it involves a search for the mysterious 野人 of 神农架? Personally, I love the description:

Noah Shachtman caught this story from Flight Global over at Wired’s Danger Room blog:

German-headquartered SIM Security and Electronic System says it has sold an undisclosed number of its Sky-Eye quadrotor UAVs into China for use by a civilian police organisation. Total sales of the existing system, including the Chinese orders, have exceeded 30 units according to Yves Degroote, Brussels account manager for the firm.

Noah says:

Sales of drones are tightly controlled by the International Traffic in Arms Regulations, or ITAR. Companies usually have to get special clearance to market the things — even in friendly countries. I’m no ITAR expert, but I believe sales to countries like China are even more carefully monitored. About a year ago, officials at Yamaha in Japan were busted for shipping nine robo-copters to the Beijing regime.

Does anybody have any idea how you say “quadrotor UAV” in Chinese? Or would these just be called 天眼 after the brand name?

UPDATE: It’s China time in the Danger Room as Sharon Weinberger points to an English People’s Daily article on Chinese scientists success at controlling the flight of pigeons with brain implants. But they don’t have a picture, so I’ll help by adding the Chinese article.

Since China is rather short on pigeons (at least not in cages), obviously these are for overseas operations. The robocoptor won’t be noticed on the streets of Shanghai, but free flying pigeons would probably surprise the hell out of people. Check out the Shangdong Science and Technology University Robot Research Center website for things like the Electrical Powerline Repair Robotic Arms and other stuff that, so far, is nowhere near as cool or gross as a pigeon with a chip in its skull.

Back in 2004, a news surfaced about CCTV producing it’s first ever science fiction TV show, Angel Online (天使在线). Sina.com.cn had a whole page devoted to it, complete with quote from the director and Chinese scifi writers talking about the need for science fiction in encouraging creativity, and how this would be China’s Star Wars, Matrix and Heat Vision and Jack rolled into one. (You can read a synopsis here, in which artificial intelligence “Net Babies” (网婴) become all the rage, only for one becomes all-powerful on the Internet). And then it became impossible to find anymore news about it – and not only because 天使在线 is the name of a popular MMO gaming webpage. Then I noticed that Seed Magazine’s China Science section mentioned it last September, and I figured I’d check Baidu again. Turns out in January Sina reported that Jackie Chan might join the show?!?? I’ll believe it when I see it, since in 2004 principal photography was suppose to start in 2005 and now Sina says it’ll be out in 2008. But in the mean time, it turns out a major fan has been working on a Chinese machinima movie: 原始地带 ZONE OF BARBARISM! You can watch a short confusing clip here, which consists of helicopter animations, the back of a head that could be Chuck Norris, and a gorilla. Perhaps it involves a search for the mysterious 野人 of 神农架? Personally, I love the description:

In the movie Karmic Mahjong, or 血战到底, that is. Jia Zhangke (贾樟柯), film festival darling and director of the recent Still Life (三峡好人) is pictured here being arrested by none other than Wang Xiaoshuai (王小帅), director of Beijing Bicycle (十七岁的单车). You can see the brief cameo scene, with JZK as a hostage-taking mugger and WXS as negotiator at tudou.com about 3 minutes in.

Captions, anyone?

UPDATE: Also of interest, Little Bridge has a post about a Chinese woman who has advertised online that she will carry someone’s baby to term for 500,000 yuan. Curiously enough, there is a character in 血战到底 who regrets carrying and then giving up her son to a mobster… for 500,000 yuan. Life imitates art? Has this girl seen 血战到底?

We interrupt our regular discussion of more fun things to discuss reports about terrorism in Xinjiang. This time, there’s an essay in the PacNet newsletter, available at the Time Magazine China Blog, by one Martin I. Wayne, a China Security Fellow at the National Defense University’s Institute for National Strategic Studies. Dr. Wayne, however, is a hard man to find. Not only is he not listed on the INSS staff directory, he doesn’t show up anywhere on Google. Not an easy feat these days. His book, “Understanding China’s War on Terrorism”, brings up nothing as well. It’s a shame, because I’d like to know more of his findings. On with the fisking (I’ve changed it so Wayne is in italics, I am not):

Al Qaeda’s China Problem by Dr. Martin I. Wayne

Al Qaeda has a China problem, and no one is watching. Despite al Qaeda’s significant efforts to support Muslim insurgents in China, the Chinese government has succeeded in limiting popular support for anti-government violence.

I have yet to see, beyond the occasional lip service provided in roughly two video statements (one here, transcrit of Zawahiri’s 2006 statement at Laura Mansfield’s site), “significant support” by Al Qaeda documented publicly by anyone.

The latest evidence came on Jan. 5, when China raided an alleged terrorist facility in the country’s Xinjiang region, near borders with Pakistan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan. According to reports, 18 terrorists were killed and 17 were captured, along with 22 improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and material for thousands more.

IEDs is a misleading term. First because IED has now become the common term for roadside bombs. Second because the term used by Xinjiang officials has been 手雷, which literally refers to “hand thunder”, or a grenade. IED in Chinese, according to press reports, is 路边炸弹, or literally “roadside bomb”. Chinese reports about the seizure of 手雷 in Xinjiang have been curious, as statistics appear contradictory. A brief review:

Chinese reportage on terrorism is notoriously problematic, at times imprecise, or simply fabricated.

… now why on Earth might one think that?

For the skeptics, photos of the policeman killed in the raid were also released, showing emotional relatives amid a sea of People’s Armed Police paying their final respects. Ironically, China’s ability to successfully kill or capture militants without social blowback demonstrates the significant degree to which China has won the population’s “hearts and minds,” however begrudgingly.

And here the author chooses a terrible phrase to use. While one could argue that the PRC has successfully prevented widespread insurgency or unrest since 1997, winning “hearts and minds” is not what most visitors to Xinjiang will mark. The hearts and minds are quite against the Chinese, as a government and as a people. It is not a zero-sum game between a) the Party and b) violent ideologues. Most Uyghurs are neither, but Dr. Wayne has chosen to omit this.

China’s successful efforts to keep the global jihad from spreading into its territory present a real challenge for al Qaeda. The organization reportedly trained more than 1,000 Uyghurs, a Turkic ethnic group that is predominantly Muslim, in camps in Afghanistan prior to 9/11. In late December, al Qaeda’s number two, Dr. Ayman al-Zawahiri, called for action against “occupation” governments ruling over Muslims, including reference to the plight of Uyghurs in western China.

The number of Uyghurs trained in Afghanistan is not easily obtainable, for obvious reasons. According to Strategic Insights, a monthly electronic journal produced by the Center for Contemporary Conflict at the Naval Postgraduate School, Gaye Christoffersen wrote:

“Beijing’s estimates of the extent of al Qaeda influence were overstated, with claims that there were 300 Uyghurs in Afghanistan in late 2001 and that all Uyghur separatists in Xinjiang were linked to al Qaeda. Later this was reduced to claims of 100 Uyghurs in Afghanistan, and altogether 1000 Uyghurs in Xinjiang trained by al Qaeda and the Taliban. That claim is supported by the United National Revolutionary Front of East Turkestan (UNRF), which also claimed that there were more than 100 Uyghurs in Afghanistan at that time helping the Taliban.”

This would be a good time to mention that the Chinese government has, as Dr. Wayne may be doing here, conflated different Uyghur terrorist organizations. The PRC has primarily referred to the East Turkestan Independence Movement, or ETIM – the only group linked to Al Qaeda through its now deceased leader Hasan Mahsum, who was killed by Pakistani forces in 2003 during a raid on an Al Qaeda hideout. Here I refer to probably the most authoritative document existing about evidence of Uyghur terrorism, Violent Separatism in Xinjiang: A Critical Assessment(PDF) by James Millward. In analyzing the 2002 8,000 Character Essay conservatively titled “East Turkistan Terrorist Forces Cannot Get Away with Impunity”, Dr. Millward points out:

“Because in Chinese the compound “Dongtu” (East Turkistan) is used both in a generic sense, for all “East Turkistan” groups, and as a specific abbreviation for any name beginning with “East Turkistan,” the result is ambiguity over whether a given act was committed by a specific group known to espouse a separatist line (such as the East Turkistan Liberation Organization, or ETLO) or by unknown perpetrators whom the authors of the document claim, without providing evidence, to be East Turkistan separatists. Moreover, the English version of the document uses the singular form (“the ‘East Turkistan’ terrorist organization”) for terms that in Chinese (which lacks a definite article) are generic and possibly either singular or plural. The document thus implies that there is a unified East Turkistan terrorist organization of considerable strength. From all other indications, however, this is not the case.”

Millward goes on to point out that US government endorsed this sloppiness when it placed the ETIM on the terrorist watch list “thus attributed to ETIM specifically all the violent incidents of the past decade in Xinjiang that the PRC document itself blames only on unnamed groups or on ETLO.” As for the UNRF, the only other source to support the 1,000 trainee claim besides the PRC, Millward notes: “the 80-year-old leader Mukhlisi is now largely discredited and resented by other exile Uyghur groups in Central Asia for exaggerating Uyghur involvement in militant activities—as he did, for example, in March 1997 by announcing that the Urumqi bombings (on the day of Deng Xiaoping’s memorial) were the work of his own and two allied Uyghur groups in Kazakhstan, by all accounts a false claim not even credited by the PRC.”

There is also a question about to what extent the Chinese government attributes what might be criminal acts for financial or other motives. The Yining Riot, also discussed in Millward’s essay, is a clear example. There has never been any evidence submitted that suggests that any sort of terrorist group was involved except PRC allegations that the East Turkestan Islamic Party of Allah provoked it (the ETIPA does not seem to exist beyond this one-off). Dr. Wayne would seem to have failed to differentiate between the claims of the PRC, the UNRF and others, and perpetuated a dangerously oversimplified picture.

Yet despite this commitment of resources and rhetorical energy, Uyghurs across Xinjiang’s social spectrum explain that violent resistance is no longer a viable path. Many Uyghurs in Xinjiang believe that insurgents worsen Uyghurs’ plight by making the Chinese more fearful, thereby more repressive.

This is, in my opinion, a fair and accurate statement. I would certainly not, however, characterize it as winning “hearts and minds”. This is what people crushed by authoritarian repression and fear say. They respond out of fear of what the PRC would do to them, not out of respect (unless you are someone who believes fear is the only form of respect, as regrettably some American conservatives apparently do). Most importantly, Wayne makes a very large mistake: he conflates the Uyghurs with both Al Qaeda and Iraq. Al Qaeda and Iraqi insurgents are not the same to begin with, and comparing it to the Uyghurs is even worse. The Uyghurs, as Millward points out, have long had ethnic nationalist aspirations, as opposed to religious ideological ones. He states:

“The participants in acts of anti-Chinese resistance and their motivations have been varied. Insofar as there is a common denominator, for the twentieth century this has been Uyghur nationalism—sometimes colored by Islam as a basic part of Uyghur culture but not arising from a desire to create an Islamic state per se.”

And this is precisely why Al Qaeda is not a good model for considering Uyghur terrorism, such as it is, and especially inappropriate for judging the views of Uyghurs who do not support violent or ideological means. Uyghurs overwhelmingly harbor nationalist dreams connected most intimately to Turkey, not the Arab states. Pan-Turkicism is an ethnic phenomenon that goes against Al Qaeda’s most basic beliefs. Islam has usually taken the role of garnish, not main dish. Millward then goes on to explain why it’s so tempting to look at Xinjiang through an Islam-centric lens:

“Despite this ethnonationalist, as opposed to religious, basis to Uyghur separatism in Xinjiang, journalists seem to take interest in Xinjiang primarily because it is a majority Muslim area. The reasons for this are clear. I myself once cowrote a magazine article titled “Why Islam Troubles China Too,” capitalizing on the fact, startling and intriguing to a general readership, that China has a large Muslim population in Xinjiang. This fact serves as a perennial hook for pieces about Xinjiang and the Uyghurs, one that seems even more compelling in the aftermat of the 2001 terrorist attacks in the United States, because it fits Xinjiang into the ongoing global narrative of “Islamic terror.” Since stories about Xinjiang usually appear as sporadic features, rather than part of continuing coverage, journalists return to this hook repeatedly with each piece about the region.”

This is part of what I consider the Xinjiang strain of “I Can’t Believe It’s Not China!” journalism.

Why Uyghurs have not radicalized in large numbers is a matter of debate, but certainly one reason is they have not been given the chance – and this is because of China’s strict control that Dr. Wayne claims has been relaxed in exchange for “soft power”. While the PRC may have eased on mass arrests or excessive force, they have not relaxed when it comes to strictly policing religion and free speech. When imams are trained by the state and surveilled, it makes it quite difficult for one of them to preach an extremist message. On the other hand, it makes it impossible for anyone to engage in civil society building or public debate. Dr. Wayne clearly understands this: “The Chinese government purged separatist sympathizers from local governments and attempted to remove political dissent from religious worship“, yet seems to believe that this control has somehow slackened. It has not, just has similar control has not slackened for any other part of the PRC (though it may be more rigid in Xinjiang).

At the same time, availability of Uyghur language education was broadened and Beijing sought to expand economic development in Xinjiang, which was viewed as the key to success.

Dr. Wayne seems unaware of the growing pressure for Uyghurs to study in Chinese language schools. He also continues on about Zawahiri’s message, which mentioned Xinjiang briefly in a list including Chechnya and Spain. He also spent several paragraphs talking about Palestine, but Al Qaeda has yet to show a very strong presence in the Territories. In fact, Hamas has told him to please go away. Another melodramatic bit of flair Wayne uses is to claim “Local men who traveled to Afghanistan to fight the Soviets returned home with new skills and attempted to ply their trade. Young Uyghurs were inspired by the power of men, armed with Allah and AK-47s, to defeat a superpower.” A number of Uyghurs, however, fought on the Soviet side. I met one in Urumqi who had a Russian tank tattooed on his chest – because he was in one. He was part of the large exodus of Uyghurs to Soviet Central Asia who eventually returned after the 80s.

The raid in Xinjiang upon a group taking mining explosives and building IEDs represents a threat similar to the attacks of Madrid and London: home-grown individuals, radicalizing, building weapons with supplies at-hand.

This sort of blurring of distinctions is precisely one of the biggest problems with the “War on Terror”. To compare angry young immigrant populations inspired by extremists zealots to an angry indigeneous population demanding political freedom is to miss the very key elements necessary to understanding what is going on.

The contrast between China’s project in Xinjiang and U.S.’s actions in Iraq is stark: where China realized that local politics was a key factor for strategic effectiveness, the U.S. has focused on targeting an ever-growing pool of insurgents and terrorists. China’s ultimate success in frustrating al Qaeda’s designs on Xinjiang rests upon its recognizing and responding to the political nature of the threat.

And so we come to Iraq, and here is the biggest failure to make a distinction I could possibly imagine. On the one hand we have China’s “project in Xinjiang”, which is to maintain control over an internal province so as to permanently keep it within their borders under an authoritarian government. On the other hand we have America’s “actions in Iraq”, where the goal, ostensibly, is to leave after establishing a democratic, self-governed nation. China’s efforts in Xinjiang have to been to prevent any kind of unified social movement, whether it be Rebiya Kadeer’s peaceful one or Hasan Mahsum violent one, so that society is organized by Beijing, not the public. If the U.S. wants to make Iraq into a repressive version of Puerto Rico, then Dr. Wayne is right – there are lessons to learn from the PRC.

OK, OK, back to more fun stuff.