Just a quick note, since I’ve been lax in Xinjiang blogging, everybody should be reading The New Dominion. They’ve got it all covered, from the newest announcement of suicide bombing food poisoning kidnapping terrorists, to the alleged Hizb ut-Tahrir connection, to telling Nicholas Kristof he’s a hack. And Uyghur lessons (podcast, fellas, podcast!!!). Now I would just make a request: hey guys, how about digging into the Uyghur forums and translating some of the stuff there? I heard there’s some wacky story getting posted all over the place about a Korean missionary who sleeps with guys in order to get them to take bibles and convert. No, really.

Month: April 2008

The Nationalist Mote in One’s Own Eye

A joint Sino-Japanese documentary, “Yasukuni” (靖国) is having some trouble finding cinemas willing to show it, apparently due to pressure and threats from right wing groups who believe the movie is Anti-Japan. The director had this to say:

“‘Anti-Japanese’ was a phrase that was used here [Japan] often before the Sino-Japanese War,” the director says.

“It was used to encourage nationalism. It’s a very dangerous phrase. Those who use it are irresponsible.”

*thump* *thump* *thump* *thump* *thump* Don’t mind me, I’m just banging my head against this wall here…

Today’s SchizOlympics Moment of Zen

From King Kaufman’s Sports Daily at Salon.com, reporting from the SF protests:

A young man dressed as the Dalai Lama stumbled through the crowds along the barricades lining the curb in front of the Ferry Building. He was moaning. Another man walked behind him, waving a Chinese flag and hitting the ersatz Dalai Lama with a rolled-up magazine. “Get out of here!” the second man yelled as he swung.

“Yeah!” yelled a Chinese woman who saw them. She waved her red flag at the men. “Good job! Good job!”

A man with a South Asian accent turned to his friend. “I don’t think she got it,” he said. “I think she missed the satire.”

And that was your SchizOlympics Moment of Zen.

SchizOlympics: Deutschland Edition

The Yellow Spies

Reading the translation on ESWN of Encounters With a German is absolutely depressing. It’s like a stage play version of everything I long feared and has now gone full blown about the huge collision between Chinese and Western worldviews and our inability to communicate. To recap, a young Chinese woman (?) living and working in Germany winds up in a nasty, bitter tat-for-tat with a German colleague. In escalating volleys of angry vindictive remarks they descend into a battle of name-calling over whose government and media is a liar. To wit:

SchizOlympics: The Web Map

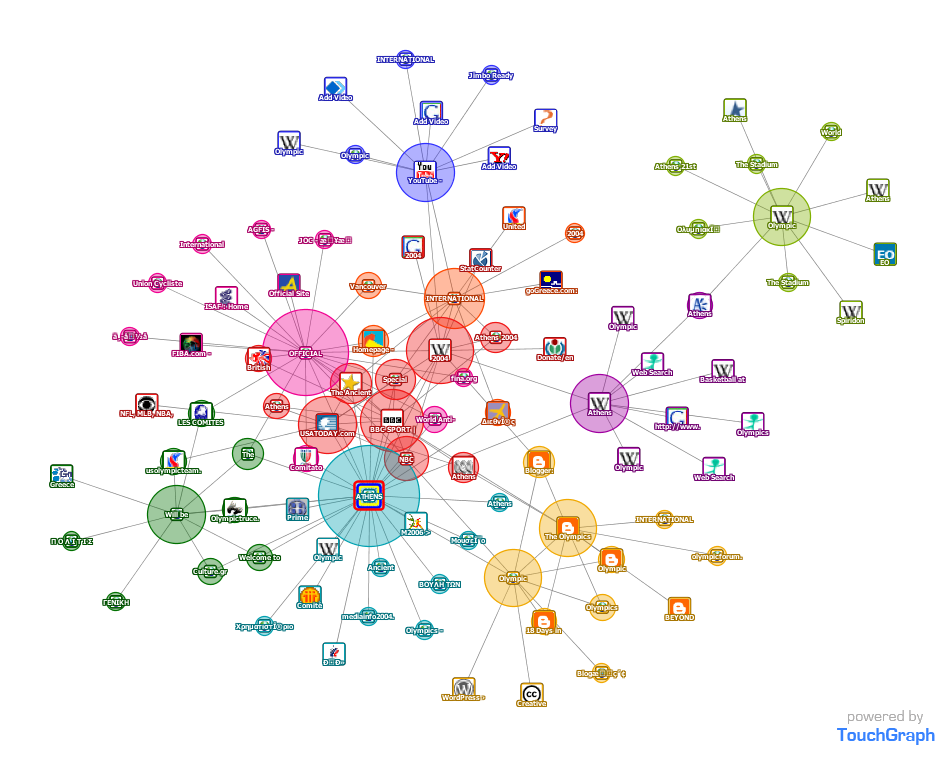

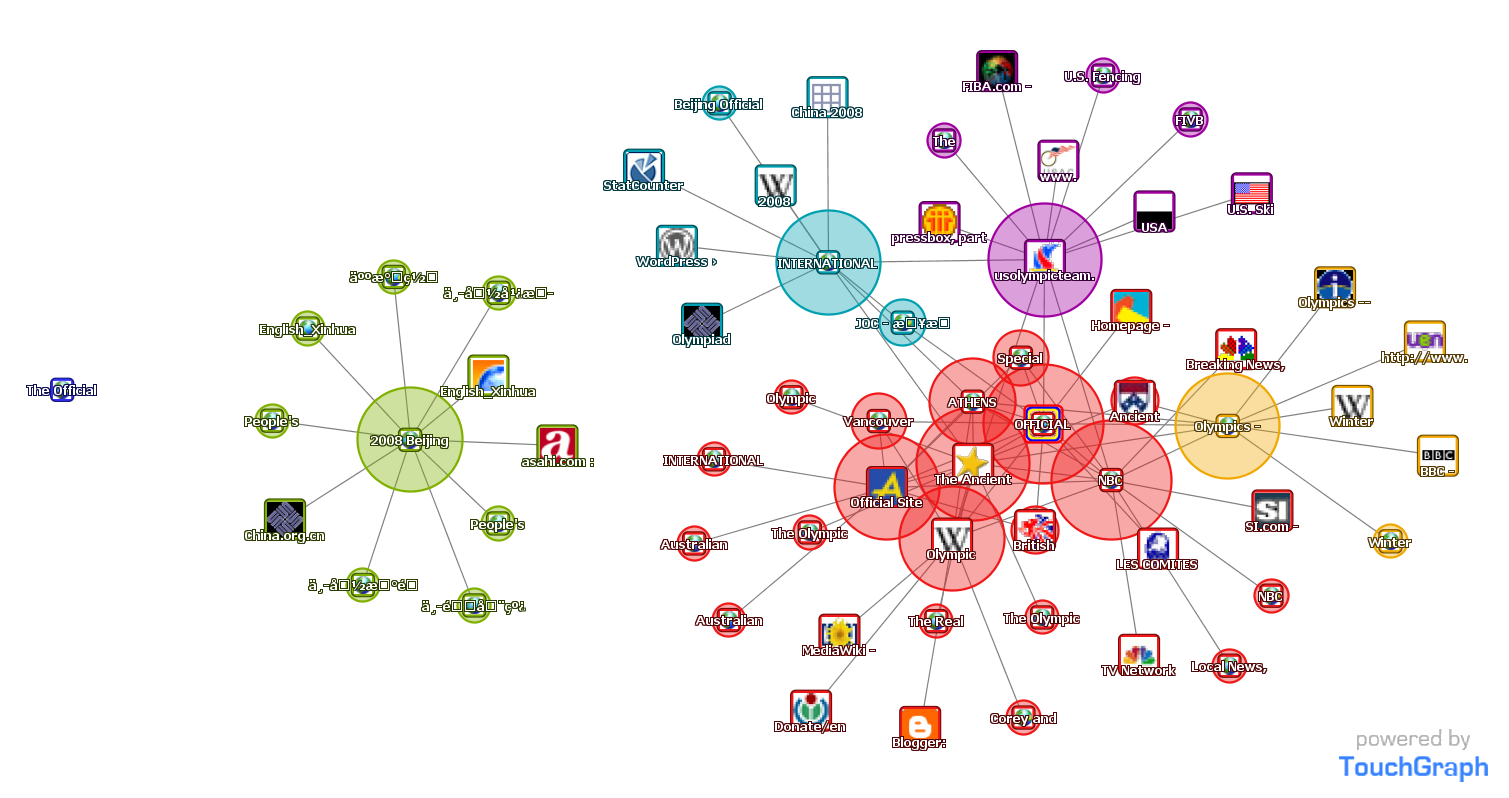

The Touchgraph for the “Beijing Olympics”

The TouchGraph Google Browser reveals the network of connectivity between websites, as reported by Google’s database of related sites.

The image above, made with the Touchgraph Browser, is a result of the search for the term “Beijing Olympics”. Click for a larger image in a separate window. The green wheel is made up of Chinese websites, in English, referring to the Beijing Olympics. They have no discernable links to the other hubs, which include the IOC, the official site of the Olympic Movement, the official site of Athens 2004, the US, UK and Australian Olympic associations and teams, Wikipedia, NBC and others. Touchgraph is clearly not an exhaustive search of links and edges between major websites, but this is notable, especially when compared to the map for Athens 2004:

Athens2004.com is the big blue circle with links surrounding it in various languages. This is remarkable especially because Athens 2004 is a dead site.

So what does this mean? Well, Touchgraph measures connectivity, though they don’t specify what precisely that means. It is some sort of calculus of the links in both directions between two webpages, and stops drilling down relatively quickly. But given the same calculus for each Olympics, its interesting that practically none of the sites that exist in China, written in English, are linked to or from the major English Olympics sites outside China. China may be coming out to the world this Olympics, but apparently their webpages haven’t.

Tuning Out: Anti-CNN and Al Jazeera

The Sina.com petition against CNN and BBC has hit over 1.6 million signatures as of this writing, and will probably close out at 2 million before the weekend is over. I find the whole thing funny because I don’t understand how anyone can take so seriously a network that offers programs like MainSail, or Larry King Live for that matter. With the recent news of Dave Marash’s departure from Al Jazeera English, I can’t help but notice that AJE is still not available from any US cable or satellite provider, though available in 100 million households in 60 countries.

The Al Jazeera Arabic parent network has been condemned in the past by members of the US government, most famously Donald Rumsfeld’s remark in April 2004: “I can definitively say that what Al Jazeera is doing is vicious, inaccurate and inexcusable.” What Al Jazeera was reporting, and showing in graphic images, that upset Rumsfeld so much was that many civilians were being killed in U.S. bombings. Rumsfelds comments echoed senior military spokesperson Mark Kimmitt who said a few days before “The stations that are showing Americans intentionally killing women and children are not legitimate news sources. That is propaganda, and that is lies.”

Conservative Americans have criticized Al Jazeera, both Arabic and English, for being a “mouthpiece for Al Qaeda” and a source of anti-semitic and anti-US propaganda, though others have pointed out that its hardly more biased then other global news networks. American cable providers probably don’t carry it because 1) there isn’t a huge outcry to carry it and 2) some of the conservative groups campaigning against Al Jazeera would launch protests and boycotts. Meanwhile, even Israelis, whose government has criticized the Arabic network in the past, have access to Al Jazeera English, and for six years the US cable provider Time Warner has carried CCTV-9, which is good and truly a mouthpiece it there ever was one.

Now ex-AJE correspondent Marash says there’s still an important reason to watch Al Jazeera English:

But you know, the thing that I loved best about the original concept was the sort of fugue of points of view and opinions, because I think that’s what desperately needed in the world. We need to know, for example, in America, how angry the rest of the world is at Americans. Our own news media tend to shelter us from this very unpleasant news. So if you watched and every piece seemed tendentious and pissed you off, and I don’t think that would be the case, but even if worst case the channel turned shrill and shallow, you would still want to watch them on the principle that millions—tens of millions—of people watch them every day and you need to know what’s going on in their brains.

This is precisely the sort of argument that many would make about CNN and BBC to those on the Chinese Mainland: Chinese people may disagree with it, even hate it, but their own news media tends to shelter them from unpleasant news and its important that Chinese people know what the rest of the world is thinking, just as Americans need to know what the Arab world is thinking, and so on and so on. It’s worth remembering, though, that China’s not the only place where people only seek out voices just like theirs.

Hu Jia & His Poem

Highlight the text below. This is an experiment created with highlite, via BoingBoing. Poem here. More on Hu Jia here.

Presently as I confront prison walls, Now I write this poem for you, my Love, my Lady, my Wife. Even tonight, the stars glitter in the cold sky of apparent isol ation. Glowworms yet appear and disappear among the shrubs. Please explain to o ur child why I did not have a chance to bid her farewell. I was compelled to emb ark on a long journey away from home. And so, everyday before our daughter goes to bed, And when she awakes in the morning, I will entrust to you, my Lady, my L ove, my Wife: I entrust to you, my warm kisses on our daughter’s cheeks. Please let our child touch the herbs beneath the stockade. In the morning on a beautif ul sunlit day, If she notices the dew on the leaves, She will experience my deep love for her. Please play the Fisherman’s Song every time you water the cloves . I should be able to hear the song, my love. Please take good care of our silen t but happy goldfish. Hidden in their silence are memories of my glamourous and turbulent youth. I tread a rugged road, But let me reassure you: I have never s topped singing, my Love. The leaves of the roadside willow tree have gradually c hanged colour. Some noises of melting snow approach from afar. Noises are engul fed in silence. This is just a very simple night. When you think of me, please d o not sigh, my Love. The torrents of my agonies have merged with the torrents of my happiness. Both rivers now run through my mortal corpse. Before the drizzle halts, I would have returned to your side, my Lady. I cannot dry your tears whi le I am drenched in rain; I can do so only with a redeemed soul after these time s of testing.Presently as I confront prison walls, Now I write this poem for you , my Love, my Lady, my Wife. Even tonight, the stars glitter in the cold sky of apparent isolation. Glowworms yet appear and disappear among the shrubs. Please explain to our child why I did not have a chance to bid her farewell. I was com pelled to embark on a long journey away from home. And so, everyday before our d aughter goes to bed, And when she awakes in the morning, I will entrust to you, my Lady, my Love, my Wife: I entrust to you, my warm kisses on our daughter’s ch eeks. Please let our child touch the herbs beneath the stockade. In the morning on a beautiful sunlit day, If she notices the dew on the leaves, She will exper< ience my deep love for her. Please play the Fisherman’s Song every time you wat

The Wolf Trap

You walk into the room

With your pencil in your hand

You see somebody naked

And you say, “Who is that man?”

You try so hard

But you don’t understand

Just what you’ll say

When you get home

Because something is happening here

But you don’t know what it is

Do you, Mister Jones?

– Ballad of a Thin Man, Bob Dylan

I lived in Xinjiang for three years. The yawning chasm between Uyghurs and Hans I saw on a daily basis in Xinjiang was disturbing, and I’m not even talking about divisions in economic opportunities or political power. I taught at a university in Urumqi, where large swaths of my Han students, though they ate Uyghur food and had lived there all their lives, didn’t know any of the dishes names in Uyghur. This struck me as being the equivalent of living in Southern California and not knowing the word “burrito”. On the eve of the Iraq war, administrators at another school told six of us, 3 Americans, 2 Australians and 1 Canadian, all Caucasian, not to leave campus after Bushs deadline, because “Uyghurs are Muslims, Iraq is Muslim”, and we would be targets of resentment and hostility. We laughed, because every Uyghur we knew hoped, not very secretly, for the US to liberate them from the Han*. Much later, at the university, I had beer with a colleague in the Foreign Languages Department. He asked if I was ever worried living amongst so many Muslims. The beer made me blunt “They don’t hate me. They hate you.” He was speechless. A Singaporean friend who was with us later said “You shouldn’t have said that. You’re right, but he can’t handle that and you know it.” I was frustrated, though. Vast numbers of Uyghurs would confess to any foreigner readily their worldview, which certainly didn’t match what Han Chinese believed. But between Uyghurs and Han, there was silence. As the Wall Street Journal reports, “One Uighur man working in Shanghai, when asked how Uighurs feel about government policy, said: “I can’t tell you the truth. It would be illegal.””

I’ve never been to Tibet, but I hear echoes of the same problems from Lhasa. I have no problem believing that Tibetans targeted violence at Han and Hui in Lhasa, for much the same reasons they are disliked in private by Uyghurs. In ESWN’s translation of a Han girls experiences How Can I Forget March 14, Lhasa?, the writer says the following:

I thought that I would be the same way with my Tibetan friends as before and not changed as a result of March 14. But as I sat in the Tibetan sweet tea house, I realized that everything has changed. The Tibetan service workers ignored the Han people completely and they only chatted with their Tibetan friends. Even worse, the Tibetans were swapping rumors and lies that completely distorted the facts. It was absurd that anyone can believe these bare-faced lies and regard them as the truth.

The reason why they believe that these were the facts is very simply that the tellers were Tibetans! They said, If you can’t trust a Tibetan, who can you trust? In any case, as long as it is a Tibetan, they you must help him no matter what the rights or wrongs of the matter are! Among their beliefs, there are no rights or wrongs and there is only ethnicity! There was no way for us to communicate!

The girl believes that what changed after March 14 were the Tibetans. I don’t think so. I think what changed is that she got a glimpse of what Tibetans have often said in private, and now dared to speak publicly. She says she “cannot forgive those criminals for destroying our homes, for destroying our lives, for destroying the brotherhood of Han and Tibetan, for destroying our trust…” I truly doubt that trust was there. Instead there was an uneasy peace maintained by silence. There was no communication of Tibetan grievances because they were suppressed.

Richard Spencer points out that much of this is because “those dependent on what the government has to say saw only soft-focus pictures of smiling folk dancers and peasants improving their lives through money funnelled from Beijing. That many Tibetans resented the Chinese would have seemed at best incomprehensible and at worst racist to an audience brought up on an ideologically correct vision of China’s ethnic minorities living in harmony.”

Shenzhen Fieldnotes had a timely post about the visit of teachers from Xishuangbanna, an ethnic enclave in Yunnan, to her elementary school. The minority teachers “arrived in “native” costumes which they wore the entire week. as far as i could tell, they weren’t wearing traditional clothing, but actual costumes that one would wear on stage to perform one of china’s 56 ethnic groups. these costumes included christmas garland and plastic flowers to adorn the women’s hair. Nevertheless, several of the han teachers told me that this is how ethnics dress, even when working in the fields. when i expressed sceptism, it was as if i had challenged something fundamental about being Chinese.”

She did challenge something fundamental about being Chinese. It’s in this context that academics say like this:

“The Communist Party has used nationalism as an ideology to keep China together,” said [Dibyesh] Anand, a reader in international relations at Westminster University in London. He said many Chinese regard the Tibetan protests “as an attack on their core identity.”

“It’s not only an attack on the state,” he said, “but an attack on what it means to be Chinese. Even if minorities don’t feel like part of China, they are part of China’s nationality.”

The Han official that accompanied them tells that he always urges them to maintain their traditions (with plastic flowers, apparently) in the face of modernization, which is curious since Han Chinese otherwise so often intensely pursue modernization otherwise, and look on less modern things with disdain. Academics such as Dru Gladney and Louisa Schein have written about how minorities in China have been commodified as exotic others, in the language of Edward Said, on which the Han can project their own modernity.

I just received a comment from a (presumably) Han Chinese person stating that Tibetans have received free medical, education and religous subsidies, and ends by saying “All Chinese People fully understand and support the policies of our government there; we should take care of Tibetan and their feelings.” Chris O’Brien at Beijing Newspeak had the perfect response to a Chinese media report arguing precisely the same thing, and which renders that final bit about Tibetans feelings incredibly ironic:

This commentary sums up perfectly the reasons why it will be a long, long time before the Chinese government gets the Tibetans on board. There is no attempt at understanding anything about what Tibetans are thinking. The argument is based purely on money and statistics. The door to discussions is closed.

I have yet to see any prominent Chinese media reports or rejoinders feature a Tibetan voice or representative, much less a Chinese Tibetan at the forefront of response to international media. But minorities in China have generally seemed to be seen and not heard.

It’s not simply the Chinese government doing this, however, but Han individuals as well. It’s not simply a top-down ideology impressed upon the masses, though the Party has certainly promulgated these sorts of ideas. The origins of this sort of thinking, where the Tibetans and others are lumped under the umbrella of “Chinese” without asking them for their honest opinion goes back before 1949. In 1927, while Tibet was essentially a de facto independent state, Sun Yat-sen discussed his Three Principles of the People, according to Frank Dikotter’s The Discourse of Race in Modern China, saying:

Considering the law of survival of ancient and modern races, if we want to save China and to preserve the Chinese race, we must certainly promote Nationalism. To make this principle luminous for China’s salvation, we must first understand it clearly. The Chinese race totals four hundred million people; of mingled races there are only a few million Mongolians, a million or so Manchus, a few million Tibetans, and over a million Mohammedan Turks. These alien races do not number altogether more than ten million, so that, for the most part, the Chinese people are of the Han or Chinese race with common blood, common language, common religion and common customs – a single, pure race.

Let’s dispense, for the moment, with the mental and semantic acrobatics that seem necessary to reconcile the words “alien”, “pure” and “mingled”. Let’s consider the fact that Sun Yat-sen was pushing a form of racial nationalism, Han nationalism, in order to “save China”. That the “alien races” are mentioned at all seems to imply that they didn’t get the privilege of pursuing their own racial nationalism. They were coming along for the ride to rescue China whether they liked it or not. And this narrative of the Chinese race faces the specter of extinction was not a new one, either. As I’ve previously written, it’s been around since the Qing Dynasty. From the late 19th century until now, it has always been a mix of racial nationalism (the resurgence of the once great Chinese, which too easily is thought of as Han), and the borders of the Qing Dynasty. The Tibetans and Uyghurs, rather sharing the sense of shame that Han Chinese have sometimes known as the “Century of Humilation” (1840-1949), in fact cherish that time as the one they wish to reclaim.

One can find the entanglement of minority and Han identity in the bestseller Wolf Totem, just released in English translation. The book centers on a young Han man who comes under the tutelage of an old Mongol herder when he’s rusticated to Inner Mongolia during the Cultural Revolution. The author Jiang Rong makes explicit analogies comparing nomads and Han to wolves and sheep, respectively, while also making the Han the bringers of thoughtless destruction via modernization. The ethnic minority, in this case the Mongols, are used as a contrast to comment on the inadequacies of the Han people. As Time Magazine’s Simon Elegant points out:

…its pleasant pastoral passages are sooner or later interrupted by jarring expositions that wouldn’t look out of place in a 19th century manual of eugenics. Here’s one from the novel’s main character, Chen Zhen:

“The way I see it, most advanced people today are the descendants of nomadic races. They drink milk, eat cheese and steak, weave clothing from wool, lay sod, raise dogs, fight bulls, race horses, and compete in athletics. They cherish freedom and popular elections, and they have respect for their women, all traditions and habits passed down by their nomadic ancestors.”

This sort of language is hardly out of place with Sun Yat-sen’s seventy five years before it, or Liang Qichao’s over a century ago.

It’s interesting to consider Wolf Totem’s condemnation of the Han as sheep when so many Han Chinese are saying themselves that the Han are still weak, weak-minded, and not capable of independent thought in response to criticism and media coverage of the Lhasa events. Clearly Jiang Rong has the pulse of the zeitgeist, and given the historical background I’ve just described, one can see how he may have gotten there.

But perhaps the most fascinating part of Wolf Totem, in this case, is what happens when Chen Zhen, obsessed with learning the secrets of the wolves, traps a cub. The Mongol community is angered at this transgression, and it also heralds the arrival of thousands of Han migrants who devastate the ecology in the name of modernization. By trapping the wolf, one really traps oneself.

———————————————

*I previously wrote about this incident, and the discrimination and ethnic tension in everyday life in Xinjiang for the Asia Sentinel.