China’s Dangerous Future? Or Poor Scholarship?

China’s Dangerous Future? Or Poor Scholarship?For a few years now, there have been periodic mentions in the press of a study on the potential threat posed by China’s impending surplus of young, unmarried males. In these stories, they have been described as a “geopolitical time bomb”, “bachelor bomb” and a threat to democracy. The source of this theory is a paper written in 2002 by Andrea Den Boer and Valerie Hudson entitled “A Surplus of Men, A Deficit of Peace: Security and Sex Ratios in Asia’s Largest States”, later expanded to book form in Bare Branches: The Security Implications of Asia’s Surplus Male Population, published in 2004. The study always seemed suspect to me, and after reading some of the supporting literature, I have a few ideas why.

Hudson and Den Boer define “surplus males” differently from “single men”, though many news articles on the topic use these interchangeably. The term “bare branches” refers to the Chinese word guanggun (光棍 ), or men without marriage prospects. Surplus males are the unintended consequence of son preference, as there aren’t enough women to go around for all of these favorite sons to marry. A “single man”, in contrast, has prospects for dating, marriage and reproduction. Bare branches are simply left out of the marriage market because supply doesn’t meet demand. Den Boer and Hudson estimate the number of surplus males by counting the difference between the number of men and women aged 15-34. By this reckoning, according to the US Census International Database, China had nearly 15 million surplus males in 1990. Using the sex ratio at birth, they estimate this will reach 30 million by 2020 – possibly 40 million if more generous birth ratios are substituted. Using the same Census tables, I calculate that current the number of surplus males is 14 million and change.*

Den Boer then go on to argue that surplus males, according to overwhelming literature, tend to be more aggressive, violent and criminal. I don’t really have a problem with arguing that unmarried single men in their twenties are often a bunch of hotheads. But they cite a study by Allan Mazur and company stating that testosterone levels, very much correlated with aggression, are higher in unmarried and divorced men. What they do not mention, however, is that Mazur’s study focuses on a reciprocal model for testosterone rather than the widely used basal model. In other words, the idea that testosterone levels are affected by being divorced or unmarried, as opposed to a man’s naturally high testosterone level affecting his chances of being divorced or married. Mazur et al. say that while the reciprocal theory better explains short-term T increases in Air Force veterans after divorce, the basal theory better explains overall likelihood of divorce. Moreover, they point out that one would expect a concentration of high-T men in lower classes, but in fact they are evenly distributed, pointing to an “invisible” stream of prosocial high-T men.

Basically, there’s a chicken-and-the-egg problem (do men lack a partner because they have high testosterone that makes them antisocial, or do men become antisocial because they have no partner?), as well as evidence that high testosterone does not necessarily make one antisocial, aggressive or violent. Like I said, I personally find it believable that young unmarried men are more likely to make trouble, but Den Boer and Hudson peg their argument on an evolutionary psychology model that seems to raise doubts.

Then there is the argument that when bare branches congregate its bad news, for which they cite David Courtwright’s Violent Land:

Men who congregate with men tend to be more sensitive about status and reputation. Even if they are not intoxicated with drink or enraged by insult, they instinctively test one another, probing for signs of weakness. . . . disreputable, lower-class males . . . exercised much greater influence in bachelor communities like bunkhouses and mining camps. They both tempted and punished, for to fail to emulate their vices was to fail, in their own terms, to be a man.

While this certainly describes, say, a frat party, it seems awfully reductionist, as does the emphasis on testosterone. Men are reduced to hormone driven robots of sorts. Den Boer and Hudson do not address factors such as family, economics, political events, moral codes, social policies or organizations, or indeed anything else that might affect the behavior of these men. I can’t help but be reminded of the dehumanizing labeling of child offenders as “superpredators” in the 1990s, or jokes about how a woman president would start a nuclear war during her time of the month.

They go on to say “It is possible that this intrasocietal violence may have intersocietal consequences as well.” This is where Den Boer and Hudson make the leap from an increase in crime due to surplus males to the supposition that it could increase the chances of war or other major forms of conflict. They give no citations, no footnotes and no supporting literature for this assertion. Instead, they then qualify their statement:

It is important to note that we are not claiming that the presence of significant numbers of bare branches causes violence; violence can be found in all societies, regardless of sex ratio. Indeed, to give but one example, the sex ratio of Rwanda in 1994 was normal. Rather the opportunity for such violence to emerge and become relatively large-scale is heightened by socially prevalent selection for bare branches. We see this factor as having an amplifying or aggravating effect. To use a natural metaphor, the presence of dry, bare branches cannot cause are in and of itself, but when the sparks begin to fly, those bare branches provide kindling sufficient to turn the sparks into a fire larger and more dangerous than otherwise.

While it is a lovely metaphor, this hardly seems a supportable claim. If they are simply stating that violence is “heightened” by the presence of bare branches, it begs the question: heightened compared to what? Remember that according to U.S. Census data, China has had about 15 million surplus males for at least the past 20 years. Shouldn’t we be seeing an increase in violence that can be demonstrably linked, or at least correlated to the male surplus population right now? There are the reports of increased mass demonstrations that are heard so often, but these have been increasing while the male surplus population has held steady, and there are plenty of other reasons for these protests (many of which involved women and older people), such as growing inequality, the rise of the Internet and cell phones, etc. etc. Plus the statistic itself isn’t at all reliable, as there are conflicting definitions of a “mass incident”. Den Boer and Hudson point to reports of high crime rates among migrant workers in China, who they believe share a large overlap with bare branches. But during this time the number of bare branches has remained steady. Other factors such as discrimination, lack of a social safety net, poor economic opportunities and the like can easily explain this. Do we even need an argument that testosterone is involved, and can this even be demonstrated?

Moreover, Den Boer and Hudson calculate it simply by subtracting the male population of 15-34 years of age from the corresponding female population. But there are other factors affecting the gender ratio. For one, prostitutes. Maureen Fan reports in the Washington Post that estimates of Chinese prostitutes range from 1 to 10 million. One estimate from 2001 mentioned by the Kinsey Institute says 3 million, which doesn’t seem unlikely. It doesn’t seem a stretch to assume that a majority of female sex workers will be in the 18-34 range, or that they are off the marriage market. Consider also that concubinage is not completely unknown at the moment and just a few years ago it was estimated that Hong Kong men alone have half a million children by mainland mistresses. So slap on another million, and you find China has been dealing with a surplus of nearly 20 million bare branches for at least a decade. Yet the effects and management of these surplus males through the years is not addressed at all in Den Boer and Hudson’s paper. Considering that China is hardly becoming instable right now due to violence, despite this surplus, one would assume that a) there is a tipping point at which the ratio becomes too imbalanced, which DB/H never suggest or b) there are some social or cultural factors at work that are mitigating the violence caused by surplus males. But DB/H explicitly state that the only way to reduce the violence is to reduce the number of surplus males, something that is not happening.

DB/H proceed to give three “suggestive” historical examples, one of which is the Nien Rebellion. A series of natural disasters led to widespread poverty and starvation in Huai-pei, which increased the level of infanticide and resulted in a sex ratio of 129 men to every 100 women, and as many as 25% of men were unable to marry at all. DB/H cite James L. Watson’s work on bachelor subcultures to point out that “unmarried men have little face to preserve because they do not command much respect in the community… these “bare sticks” had nothing to lose except their reputations for violence.” They claim that right now China is recreating “the vast army of bare sticks that plagued it during the nineteenth century”. But they quote Watson as also saying “most bare branches in his study were semiliterate and were third, fourth, or fifth sons whose families were too poor to offer them an inheritance. In many cases, these noninheriting sons were “pushed out” (tuei chu) of their fathers’ houses in their teens, and came to live in bachelor houses with groups of other unmarried youths. In their early twenties, they would move out of the bachelor house and in with a collective of men—a dormitory of workers, a monastery or religious brotherhood, or the local militia. In each case, they would spend much of their leisure time learning and practicing the martial arts.”

There are significant differences between this case study and modern China. First of all, the Nien Rebellion and the gender imbalance itself, by DB/H’s own description, were primarily the result of massive disasters and poverty. Whether the bare branches intensified the conflict seems unprovable – if you are married with a family you cannot feed, are you any less likely to join a rebel army in the hopes of providing for them? More importantly, in contemporary China, there are few 3rd, 4th or 5th sons. Most bare branches will be only or second children, and with China’s growing elderly population, it seems less likely they will be pushed out of the house to prove themselves. Rather, it seems quite likely they will be kept around the house to care for their aging parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles. If they migrate to work, they will still have parents dependent on them for support. Watson illustrates a clear role for social factors in the likelihood that these men will turn to violence – social factors that DB/H consider irrelevant later on.

And finally, monasteries and brotherhoods hardly play a role today like they did in the mid-nineteenth century. In later detailing some of the history of these groups, DB/H opine: “Given the high sex ratios of its society, perhaps the grave suspicion with which the current Chinese government views movements such as the Falun Gong is not entirely unfounded in light of this history.” The Chinese government probably does have groups like the Heaven and Earth Society in mind when they worry about Falun Gong, but it should be pointed out that Falun Gong has overwhelmingly appealed to the elderly, not angry young men. In this case it would be China’s growing elderly population that would be the source of trouble, not bare branches.

Perhaps roving bands of grannies might be the real problem

Perhaps roving bands of grannies might be the real problemThe most problematic assertion in DB/H’s paper is when they suggest that the presence of bare branches drives the development of authoritarian societies. Perhaps one could argue a surplus female population does too, since Hitler rose to power while Germany had around 2 million extra women. But here Den Boer and Hudson quote the work of Christian Mesquida and Neil Weiner: “Choice of political system made by the members of a population is somewhat restricted by the age composition of its male population.” However, they also quote Mesquida and Weiner’s conclusion:

“Our analyses of interstate and intrastate episodes of collective aggression since the 1960s indicate the existence of a consistent correlation between the ratio of males 15 to 29 years of age per 100 males 30 years of age and older, and the level of coalitional aggression as measured by the number of reported conflict related deaths.”

Mesquida and Weiner do indeed name a tipping point for major conflict, and allow for mitigating circumstances – unlike Den Boer and Hudson:

“Populations with ratios of young males exceeding 60 per I00 males 30+ are predicted to move toward a state of internal or external conflict, unless there exist particular mitigating circumstances such as an extremely rapid increase in resource availability or new possibilities to migrate to more productive environments.”

If one looks at U.S. Census data comparing the ratio of 15-34 year old males to 35+ year old males (weighing the ratio even more in Den Boer and Hudson’s favor than Mesquida and Weiner’s original age groupings) in China from 2000-2020, it is clearly steadily decreasing as China’s population grays. In 1996, the ratio of younger men to older was 104:100, which by Mesquida and Weiner’s scale ought to have provoked a major conflict. In 2005, the ratio was closer to 75:100. In 2020? 65:100. By Mesquida and Weiner’s argument, the chances of China’s sex ratio causing problems in the future are less, not more, than the past decade. Den Boer and Hudson’s references to Robert Wright’s The Moral Animal and Laura Betzig’s study of the link between despotism and polygyny (men hoarding wives and mistresses) are also questionable, since they infer that these works argue that gender imbalances are only governable by authoritarian regimes, when both seem only to suggest that there is a correlation between imbalanced sex ratios and authoritarianism – not that only authoritarianism can deal with a preponderance of men.

Den Boer and Hudson’s prescribe “there is only one short-term strategy for dealing with a serious bare-branch problem: Reduce their numbers. There are several traditional ways to do so: Fight them, encourage their self-destruction, or export them.”

The assumption here is that non-spousal family obligations, non-violent forms of single male social engagement, increased economic opportunity and other social support mechanisms count for nothing. Surplus males cannot be made into productive members of society, and therefore must be eliminated. It seems grossly reductionist but is a natural conclusion given all the ignored factors previously mentioned.

Similar criticisms have also been raised before in the Chronicle of Higher Education.

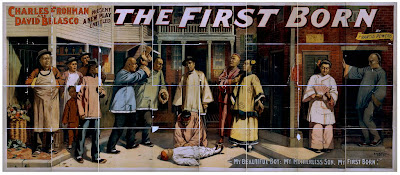

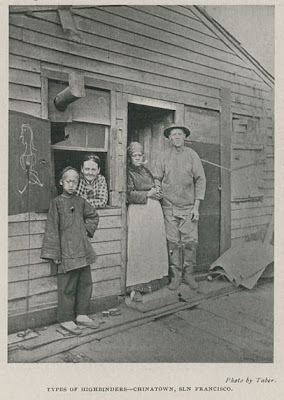

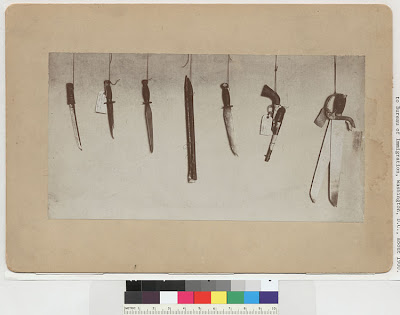

One case study that Den Boer and Hudson don’t explore at all is the Chinese bachelor subculture that existed in nineteenth century America. According to Thinkquest, “In 1860, the sex ratio of males to females was already 19:1. In 1890, the ratio widened to 27:1. For more than half a century, the Chinese lived in, essentially, a bachelor society where the old men always outnumbered the young.” Chinese immigrants did indeed represent a disproportionate number of arrests and criminal activity, but there were such aggravating factors such as the racist violence perpetrated against them. Some have argued that Chinese were still less prone to violence despite mob violence against them. Moreover, there is a great deal of evidence that “”public officials and the general public” accepted [Chinese on Chinese] “interpersonal violence … [as] to a large extent a private matter””. Den Boer and Hudson could argue that this is an example of a government (though I wonder if they would characterize California officials as “authoritarian”) allowing bare branches to destroy one another. But one could just as easily suggest that with proper law enforcement and a lack of discrimination, these immigrants would not have been anywhere near as violent. But if one accepts that these men are unstoppably driven to be violent, as Den Boer and Hudson argue, then there wouldn’t be any reason to help them.

——————————————

* It should be noted that I consulted the China Statistical Yearbook as well, but found that according to their, the 18-34 population actually has a tiny surplus of females, not males. Also perplexing was that, when totaled, the number of currently married women exceeded the number of married males by several million. To my knowledge there are nowhere near that many Chinese women married to foreigners (who remain Chinese citizens counted in the census). Anybody know why?